Australasian Bittern

Botaurus poiciloptilus (Wagler)

Ardea poiciloptila Wagler, 1827. Syst. Av., Ardea, sp. 28: New South Wales.

Other names: Australian Bittern, Boomer, Brown Bittern, Bull-bird in English; Avetoro Australiano in Spanish; Butor d'Australie in French; Australische rohrdommel in German.

Description

The Australasian Bittern is a stocky, thick necked, medium sized, mottled dark brown and buff heron with a black mustache.

Adult: The Australasian Bittern’s crown is brown. The upper bill is yellow to buff with the top of the bill dark brown to grey black, somewhat short relative to the New World large bitterns. The loral area is variable, green grey to blue grey, extending onto the lower bill. The irises are yellow. A narrow stripe of skin from the nostrils to the bill is dark olive brown. A light line above the eye is buff white. Side of the face is buff. A dark mustachio streak runs from the gape to the sides of the neck. It is dark brown near the bill becoming paler brown as it blends into the neck. The hind neck and back are dark brown with buff streaks and freckling giving a general mottled and streaked appearance. Upper wings are finely barred in buff and brown with dark brown flight feathers irregularly barred or spotted with buff. The tail is brown with buff fringes. Chin and upper throat is white with mottled brown central stripe. Lower throat and foreneck are buff white with dark brown longitudinal stripes and freckling. Belly and feathered thighs are white. Under wing is buff white with freckled brown. The legs and feet are green yellow to dark olive. There is no information on changes during courtship or breeding but it is likely that reported blue green lores and orange brown irises are breeding colors.

Variation: Females are much smaller than males but have the same plumage. However, individual plumage is highly variable. Dark, light, in-between, and red birds occur. Darker birds have a darker mustachio stripe. The upper parts are dark brown with little of the pale streaking or freckling. The dark feathers make the bird appear uniformly dark to black at a distance. Birds are also reported that are reddish, with a cinnamon buff side of face and rufous upper parts and upper wing.

Juvenile: Immature birds are similar to adults but are paler, with a yellow tinge to the basic color, and underparts streaked rufous. Iris is yellow. Bill is yellow green to olive grey with grey brown top of bill. Facial skin is light green to green yellow, with the narrow stripe between the eye and bill being black green. The legs are dark olive.

Chick: The hatchling has long sparse dark brown down. As they are older, they become buff to yellow brown above and yellow brown below with a white chin and throat.

Voice: The “Boom” call is the loud, resonant call given during the breeding season by territorial males. They start with four short quiet gasps followed by “woomph, gasp, woom”. Each call typically includes 2-3 booms. Males call back and forth to each other. The “Craak” call is a short harsh alarm call and also the flight call when disturbed. A bubbling sound is reported from a female returning to the nest. This and other vocalizations need more study.

Weights and measurements: Length: 66-76 cm. Weight: females 571-1,135 g, males 875-2,085 g.

Field characters

The Australasian Bittern is identified by its stocky build, thick neck, medium size, brown and buff mottled plumage, plain brown crown, dark brown moustache, broadly brown streaked neck and breast, and finely vermiculated and spotted upper sides. When disturbed it flies up heavily on broad bowed wings with legs dangling, and quickly plunges back down into the vegetation without circling. In full flight, this bittern flies with steady slow wing-beats, reported to be rather owl-like (Marchant and Higgins 1990).

It is distinguished from the immature Rufescens Night-Heron by being larger with a heavier, stockier build and less hunched appearance, having mottled (not densely spotted) back and upper wings. It also is not usually found in flocks nor perched in trees. Its bill is relatively shorter (shorter than length of head vs slightly longer in the night heron) (Marchant and Higgins 1990). It is distinguished from the Black Bittern by being larger, stockier, brown (not black) and upper parts. It is distinguished from the Eurasian Bittern by having darker upper parts, much darker in some, especially on the neck and back, which also are less strongly marked in paler shades.

Systematics

The Australasian Bittern is one of the four large Botaurus bitterns, which all have streaked brown plumage, scutellate tarsi, 10 tail feathers, and a booming call. It is most closely related to the Eurasian Bittern (Payne and Risely 1976, Sibley and Monroe 1990). The birds of south west Australia and New Zealand in the past have been recognized as separate subspecies.

Range and status

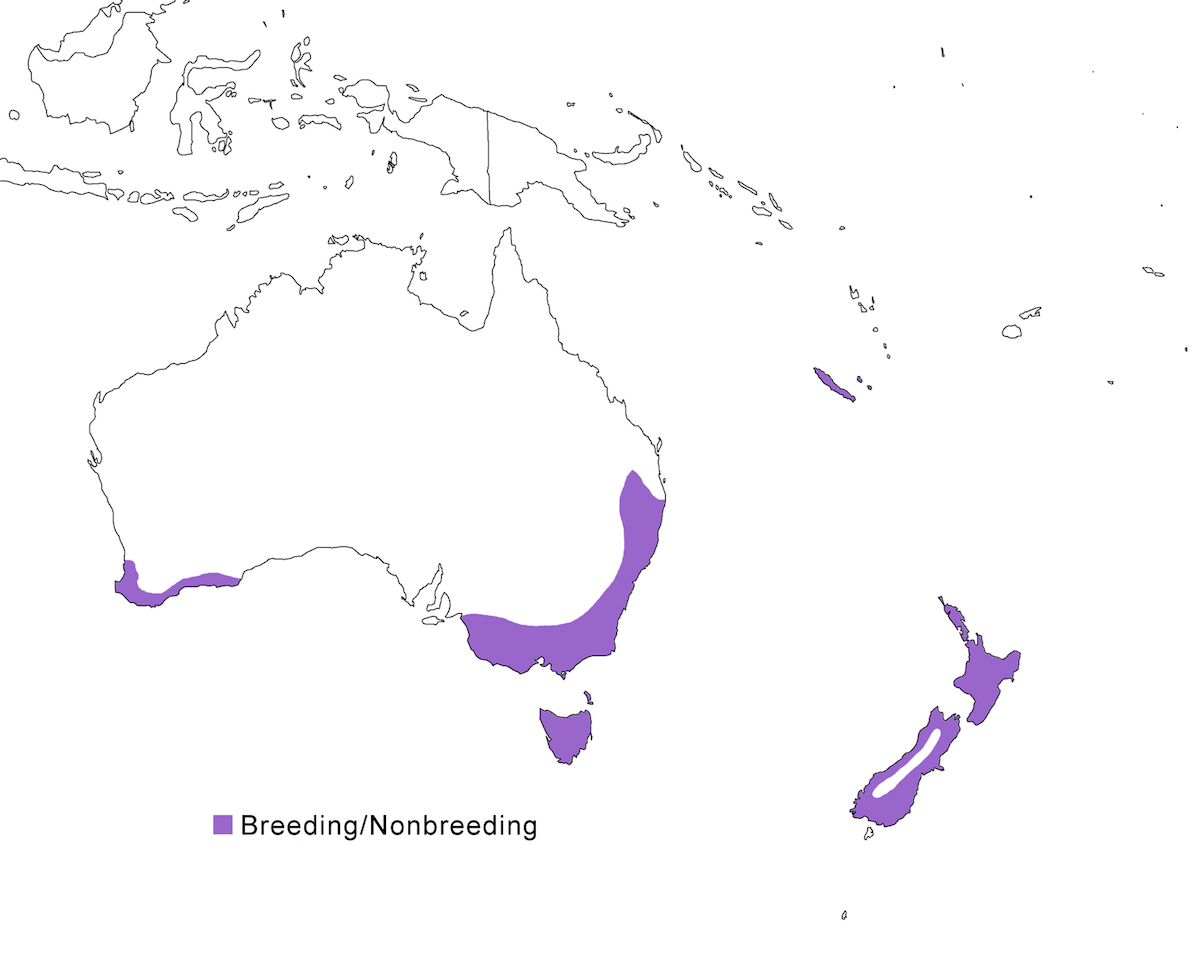

The Australasian Bittern occurs in Australia, New Zealand and nearby islands.

Breeding range: The Australasian Bittern occurs in south east Australia (south Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, east South Australia), west Australia (south Western Australia), Bass strait Islands, Tasmania, New Zealand (North Island, South Island, Stewart Island, Great Barrier Island, Mayor Island), New Caledonia and Loyalty Islands. There in fact are few records of actual breeding within this range, but it is assumed due to year-round residency.

Migration: The species is generally sedentary. It likely undertakes seasonal population shifts associated with the wet and dry season, with some suggestion of winter influxes occurring along the coasts of Australia and New Zealand (Whiteside 1989, Marchant and Higgins 1990). There also appears to be movement in exceptional dry or wet situations. Dispersal occasionally occurs, perhaps more so in the past when populations were higher in New Zealand. Dispersal birds occur in Western Australia, and on islands including Chatham Island (more frequently in the past), Kapiti Island, Great Mercury Island, and Lord Howe Island, and recently in the Torres Strait (Stokes 1983), suggesting that the species should be looked for in New Guinea.

Status: It is widespread New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia, being most common in the Murray-Darling basin and coastal areas. In Tasmania, it is most common in east. Populations in Western Australia have decreased in the last century to about 100 pairs, and it is now confined to high rainfall areas along the west coastal plain. It is widespread but thought to be declining in New Zealand. The population there is 580-725 birds. It was once common on the largest of the Loyalty Islands, but its current status is unclear and is likely extirpated. It is not clear if the Chatham Island population was resident or dispersive, but it has not been reported there since 1910.

New Zealand distribution maps for the species (Marchant and Higgins 1990, Heather and Robertson 1996) show it as occurring throughout the whole of the North and South Islands, which can be somewhat misleading (M. Maddock pers. comm.). There are mountains in the North Island and along the whole spine of the South Island that are up to more than 2,000 m in altitude, capped with permanent snow and glaciers and heavily forested on the slopes below the snow line. However, deep valleys with lakeshore wetlands suitable for the bitterns within the habitable altitude range for the species penetrate well into the mountains. For example Chambers (1989) recommends Lakes Manapouri and Te Anau, surrounded by ranges of 1,000 m or more in altitude, at the eastern margin of Fiordland, as suitable locations for observing the bird.

Habitat

The Australasian Bittern typically uses permanent fresh water marshes with dense reed and rush beds situated in shallow (less than 30 cm) water. They occur along rivers, pools, lakes and swamps. They particularly use places near the edges of pools and waterways through the marsh. Typical vegetation includes Typha, Phragmites, Juncus, Baumea, Eleocharis, Gahnia, Bulboschoenus, Ludwigia, Eragrostis and small bushes. It usually feeds and nests within the marsh, near the interface of the marsh and open water. It sometimes does occur in more open situations, on mud banks and in open water. It also uses, temporary pools, tidal marsh near the mouths of freshwater creeks and seeps, mangroves (Miller and Miller 1991), rice fields, tall wet pasture, and drainage ditches (Grant and Bennett 1986). It is primarily a bird of low land swamps but occurs to 300 m in New Zealand.

Foraging

The Australian Bittern is generally a solitary hunter, although it also feeds in pairs and sometimes in loose groups of up to 12 birds. It feeds primarily at night, but is also observed to feed crepuscularly and by day especially in winter. More information is needed on the daily cycle.

It feeds by Standing motionless, waiting for prey. It feeds from the edge of thick vegetation, from the bank, or from overhanging branches. It establishes feeding spots by flattening areas in the reeds, which often are littered with discarded remains of crustaceans and frogs. It also Walks slowly in a Crouched almost horizontal posture, moving forward with great deliberation, often knee-deep in water or along a bank. Each foot in turn is lifted high as it progresses. It frequently Neck Sways. It also has been recorded as Baiting using pieces of grass to lure fish.

On locating prey it makes a rapid Bill Strike by pivoting forward on its legs with neck and back straight (Whiteside 1989). The upper legs are short relative to the lower legs providing the pivot. They also Lunge from a crouched position, leaving the ground. The rapidly assume a Bittern Posture when encountering an intrusion but also uses it for surveillance (Whiteside 1989). When disturbed they fly up and return into the marsh quickly.

The diet is variable, but fundamentally fish (eels, trout, Crassius), frogs (Hyla), and crayfish (Cherax). The overall diet includes insects (cutworms, weevils, crickets, grasshoppers), spiders, mollusks, lizards, rats, mice, and small birds, including white-eye (Zosterops). In New Zealand the introduced Hyla appears to constitute its main prey. But in all areas, the diet has not been studied in any detail.

Breeding

Breeding is October–February, but more information is needed. It nests in reed beds up to 2.5 m tall, usually near openings such as pools or streams. It uses small to large wetlands, 5-300 ha, reportedly usually only one bird per wetland. Four and five birds were reported in 200 ha swamps, or 2/100 ha (Marchant and Higgins 1990).

The bittern is a solitary nester. However several (up to 7) nests can be found in close proximity in the same reed bed. These are assumed to belong to one male and may represent polygamous breeding. More details are needed. The nest is a platform 30-40 cm across, 20-22 cm thick. It is made of reed and occasionally grass placed within the marsh vegetation seldom more than 10-30 cm above normal water level. Females appear to build the nest alone.

The male announces and advertises its territory in the spring with its Boom Call. This far carrying call is given mostly at dawn and dusk. Circle Flights have been recorded with feet dangling. A flight display has also been described involving two birds flying alternating slow flapping and gliding. It is likely the Bittern Posture is used as a display, in which the brown mustachial streak is expanded into a ruff on either side of the head and neck.

The eggs are brown olive or green cream, average 52 x 38 mm. The clutch is 4-5; range is 3-6 eggs. Incubation starts with the first egg and is 25 days. The female alone incubates.

Renesting occurs when eggs are lost. The chicks are fed by regurgitation into the nest, apparently by the female. The chicks can leave the nest in 2-3 weeks, and begin to wander into the surrounding reeds. They fledge in about 7 weeks. Nothing is known of the nesting success of the species.

Population dynamics

Nothing is known of the population biology or demographics of the species.

Conservation

Information on status is slim because of its occurrence in dense, inaccessible habitats. Although locally common in the Murray-Darling river system, long-term population declines elsewhere in Australia and New Zealand are matters of grave concern. In Australia, declines are caused by habitat alteration-drainage, salinization, damming, grazing, clearing for agriculture, and peat extraction. In New Zealand, swamp drainage and, previously, hunting for feathers sought-after by trout fishermen caused the decline. That these two presumably isolated, declining populations have been thought distinctive enough to merit subspecific status suggests the importance of focusing conservation measures on these disjunct areas. In many ways, however, the viability of the species as a whole depends on the health of the Murray-Darling system. In west Australia and New Zealand habitat restoration may be required. Like other large bitterns, this species favors Typha marshes, and could use disturbed wetlands. Properly managed disturbed and artificial wetlands can be an integral part of a conservation strategy. In addition to protecting habitat in parks and reserves, the importance of habitat management on private land cannot be overstated (Corrick 1995). Conservation of this species needs to become a higher priority (Hafner et al. 2000). It is categorized as Critically Endangered by HSG. It is considered to be Vulnerable by IUCN (IUCN 2003). It also is a Vulnerable species in Schedule 2 (updated 1999) under the NSW Scientific Committee Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 and in Victoria, its conservation status is classified as Endangered (NRE 2000). One reason why its conservation status is inconsistent is that its actual status is surprisingly poorly known. Although its estimated world population is well under 10,000 birds (Hafner et al. 2000), it may be far smaller in that fewer than 100 pairs were surveyed in west Australia, and fewer than 800 birds estimated in New Zealand. The nesting population in southeast Australia has not been documented. Actions required include a complete survey of the breeding population in east Australia, especially in the Murray-Darling system, and New Zealand, identification of important areas (those that support 100 or more birds), development of habitat management recommendations including enhancing the use of artificial and disturbed wetlands, implementation of a range-wise strategy for habitat protection and management, and establishing a monitoring programme. Conservation should focus independently on west Australia, east Australia, and New Zealand.

Research needs

So little is known about the biology, breeding range and dispersion, behaviour, and habitat requirements of this species, that comprehensive studies of its biology are needed. Actual records of nesting are few. Surveys should be undertaken to determine the actual breeding range and dispersion of nesting across the range. Especially important are the areas where declines are occurring and also the MurrayDarling basin, which supports the majority of the population. The species’ use of Typha marshes should be carefully studied in order to determine required habitat characteristics within this marsh type. Such information can be used to develope habitat management recommendations for enhancing the bird’s use of artificial and disturbed Typha marshes. The species is highly variable in plumage characteristics. It is unclear what part of this variation is individual and what has geographic components. Intra-specific variation in plumage and morphometrics should be studied to re-examine the distinctiveness of west Australia and New Zealand populations. The results may have important conservation implications.

Overview

This is a reed-bed species. It characteristically uses patches of emergent marshes of grass, reed, or sedge, located in swamps, along rivers, or as isolated wetlands. Its habits and morphology are designed to make maximal use of concealment within the thick marsh vegetation. Its long toes allow it to support itself on the grass; its short legs, particularly the upper legs, allow it to crouch low to the water while Standing or Walking and still be able to lunge forward to strike. It eats fish, frogs, and insects, but overall has a broad diet of whatever it can encounter in the marsh. It has the potential for being adaptable in that its favoured habitat is also one that responds well to human hydrological alteration and it is able to use more open and even human-created habitats. It none the less occurs primarily in inaccessible situations, and its biology remains very much unknown.