Aberrant plumage in a Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) from the Dominican Republic

Abstract

The Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) is one of the most widely distributed heron species worldwide, absent only from Australasia and the far northern Holarctic. Notable for its pronounced phenotypic and genetic variability in plumage, the species occasionally exhibits rare chromatic aberrations such as melanism, leucism and albinism. These phenomena provide valuable insights into adaptability, underlying genetic mechanisms and ecological and evolutionary implications. Here, we summarize the frequency and geographic distribution of documented plumage aberrations of the Black-crowned Night Heron, with emphasis on melanism, and present a field record from the Copey wetlands, northern Hispaniola. The observed individual exhibited predominantly rufous wing plumage reminiscent of the Nankeen Night Heron (Nycticorax caledonicus), yet its head and neck coloration were more consistent with Black-crowned Night Heron. Based on morphology, geographic distribution and regional biogeography, aberrant plumage is considered more likely than hybridization. Genetic analysis is recommended to confirm this hypothesis.

Key words: Ardeidae, Caribbean, Copey wetlands, Hispaniola, hybridization, Insular tropics, melanism, phenotype.

Introduction

The Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) is cosmopolitan in distribution, with the exception of Australasia and extreme northern Holarctic regions (Hothem et al. 2020). Substantial intra- and inter-population variations in plumage patterns can be attributed to genetic and environmental influences. Rare chromatic aberrations—including melanism, leucism and albinism—have been documented sporadically (Pitelka 1938, Guay et al. 2012, Hothem et al. 2020, Luo et al. 2022).

Accurate documentation of such aberrations is essential for understanding species adaptability, genetic architecture of plumage pigmentation and ecological and evolutionary pressures that maintain or eliminate variant phenotypes (Sullivan et al. 2009, Ng and Li 2018, López et al. 2024). This study reports a distinctive individual observed in the Copey wetlands of the Dominican Republic and examines the likelihood of hybrid origin versus plumage aberration within the framework of species biology and biogeography.

Field Observations

On 18 September 2024, as part of the Integrated Marine Ecosystem Management (IMEM) project in northern Hispaniola, we conducted an initial waterfowl survey at a lagoon within the Copey wetlands, near the community of Copey, Montecristi Province (19° 40′ 35.58″ N, 71° 40′ 18.15″ W; population 4,000; Oficina Nacional de Estadística 2023).

The dominant vegetation is cattails (Typha sp.), water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) and other aquatic macrophytes interspersed with grasses and mesquite (Prosopis pallida) (Cano-Ortiz et al. 2018). The wetland supports several Yellow-crowned Night Herons (Nyctanassa violacea) and numerous Black-crowned Night Herons. Additional recorded species included the Roseate Spoonbill (Platalea ajaja), multiple Anatidae, Calidris spp. and representatives of Rallidae.

At 18:24 hr, LRP observed and photographed a heron perched on a mound of Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon) in the center of the lagoon (Fig. 1). The individual remained stationary for several minutes before departing for the northwest. Weather conditions included a mild breeze and 50% cloud cover.

Results

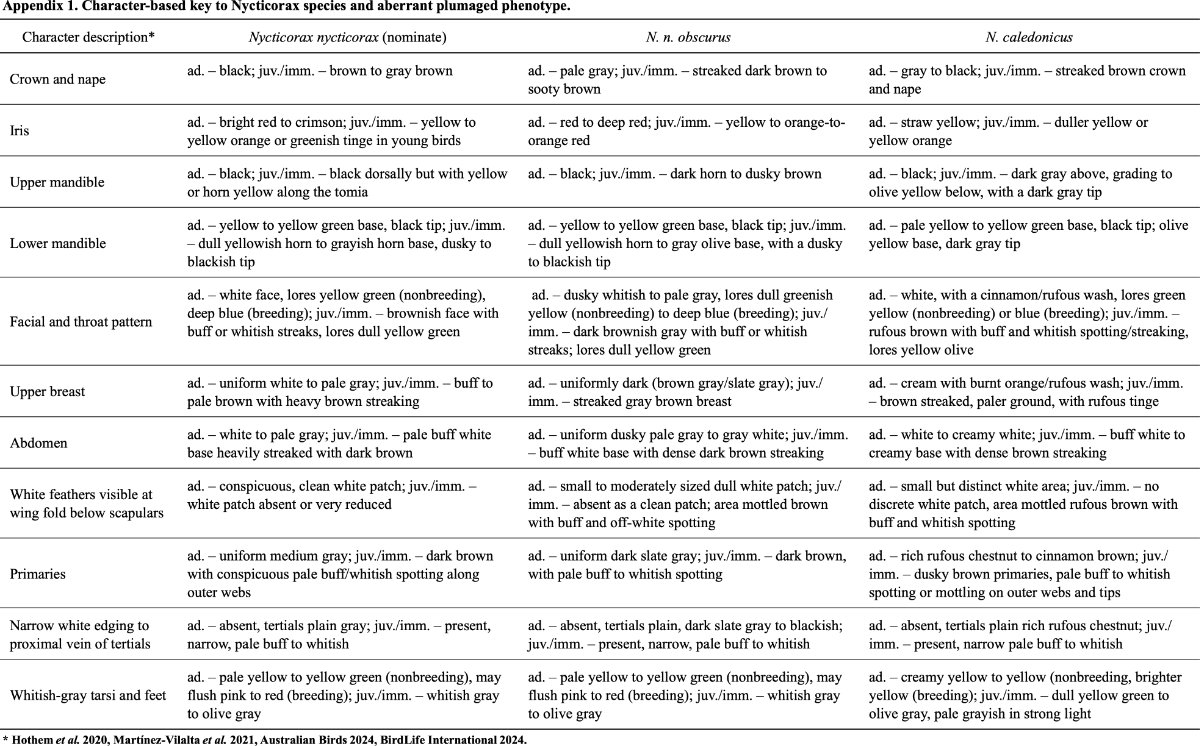

Field observations, subsequently verified through photographic documentation, initially suggested that the individual in question was a juvenile Black-crowned Night Heron approximately two years old. This assessment was aligned with general expectations for the species at that age. However, closer scrutiny revealed that several plumage characteristics diverged from those of the typical juvenile phenotype (Appendix 1). In particular, the wings exhibited a predominantly rufous tone, an attribute more characteristic of Nankeen Night Heron (Nycticorax caledonicus) (Lepage n.d., Marchant and Higgins 1990, Martínez-Vilalta et al. 2021, BirdLife International 2024), whereas the head and neck coloration remained consistent with Black-crowned Night Heron (Fig. 1). This combination of traits prompted further consideration of additional explanations, including hybridization, long-distance vagrancy and the potential involvement of escapees from captivity (Spendelow and Patton 1988).

To evaluate these possibilities, it is important to note that Nankeen Night Heron occurs naturally only within the Australasian region (Hothem et al. 2020, Australian Birds 2024), where populations are either sedentary or partially migratory (Lepage n.d., Frost 2013, Martínez-Vilalta et al. 2021). Although infrequent cases of long‑distance vagrancy in the Nankeen Night Heron have been documented (Pratt et al. 1987, Marchant and Higgins 1990, del Hoyo et al. 1992, Frost 2013, Heather and Robertson 2015), such dispersal events remain exceptional within the species’ natural history. Consequently, the likelihood of natural hybridization between Nankeen Night Heron and Black-crowned Night Heron in the Caribbean is low.

Atmospheric transport mechanisms were also assessed as a potential explanation for the presence of the night Heron. Prevailing largescale circulation patterns—most notably the subtropical jet stream—are oriented primarily west–east, making them unsuitable for facilitating interhemispheric movement from Australasia to the Caribbean (Xie et al. 2015). Likewise, trans-equatorial cyclone transport is highly improbable, as the wind regimes in the two hemispheres operate in opposing directions (Kuleshov et al. 2008). Taken together, these distributional and meteorological constraints suggest that neither natural hybridization nor passive atmospheric transport offer a plausible explanation for the observed plumage anomaly.

Discussion

From the combined weight of field observations, photographic evidence and expert consultation (H. van Grouw, pers. comm.), the Copey wetlands individual is plausibly interpreted as a melanistic, or otherwise pigment-aberrant, Black-crowned Night Heron, rather than a hybrid with Nankeen Night Heron. This hypothesis rests on the recognition that aberrant plumage phenotypes in herons can arise through well-characterized genetic mechanisms (Ng and Li 2018). Specifically, recessive alleles or mutations in pigmentation-related loci, most notably MC1R (melanocortin1 receptor), which regulate eumelanin synthesis, and ASIP (agouti signaling protein), which modulates the spatial distribution of melanin, are known to alter feather coloration (van Grouw 2013, 2017, Ng and Li 2018, Jeon et al. 2021). These genetic factors may act independently or interact with environmental factors, such as diet or habitat conditions, to produce atypical plumage expression (Ng and Li 2018).

Understanding the ecological and evolutionary context of chromatic aberrations is critical for interpreting their occurrence in herons, as recent syntheses highlight the ecological functions and evolutionary origins of plumage variation (Mason and Bowie 2020, Harris et al. 2019). Melanism has been investigated as an adaptive trait conferring crypsis (Bennett and Théry 2007, van Grouw 2017, Harris et al. 2019), thermoregulatory benefits under variable thermal regimes (Britton and Davidowitz 2023), and roles in social signaling and correlated physiological traits (Ducrest et al. 2008, Roulin 2004). Yet these advantages are not universal, as context‑dependent neutrality or even disadvantages have been documented, with melanin plasticity yielding no clear benefit in certain environments (Britton and Davidowitz 2023), pleiotropic trade‑offs constraining adaptive value (Roulin 2004) and macroecological analyses showing that melanism distributions are strongly habitat‑dependent (da Silva et al. 2017). In Black-crowned Night Heron, melanism is rare, estimated at less than 1% of the observed individuals, with higher frequencies documented in geographically isolated or demographically bottlenecked populations (Hothem et al. 2020). More broadly, other pigmentary anomalies, including leucism and albinism, have been reported in colonies in urban wetlands and coastal rookeries worldwide (Kushlan and Hancock 2005, Hothem et al. 2020), indicating that aberrant coloration is not unique to this case.

From a biochemical perspective, avian melanin pigmentation is derived from two primary pigment types: eumelanin, which produces black to gray tones, and phaeomelanin, which yields warm brown, tan and rufous hues (McGraw et al. 2004). The pronounced rufous coloration in the wing plumage of the Copey wetland bird suggests a substantial phaeomelanin component. However, without molecular data, such as targeted sequencing of MC1R, ASIP, or other pigmentation-associated genes, any definitive classification of this individual, whether as a hybrid or as a pigment-aberrant Black-crowned Night Heron, is provisional.

Given these uncertainties, the next step is to prioritize genetic sampling of aberrant individuals, combined with systematic phenotypic monitoring of Caribbean Black-crowned Night Heron populations. Such an approach would allow researchers to quantify the prevalence of pigmentary variation, map its geographic distribution and identify the potential genetic or ecological drivers.

This record is presented with two complementary aims: first, to document the occurrence of this anomalous heron, whether ultimately determined to be a vagrant hybrid or a resident Black-crowned Night Heron exhibiting pigmentary aberration; and second, to stimulate further discourse within the ornithological community. By establishing a clear public record, we also provided a reference point for comparison; similar phenotypes should be reported in the region in the future.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially and logistically supported by the USDA Forest Service, the International Institute of Tropical Forestry, San Juan, Puerto Rico, and the Integrated Marine Ecosystem Management (IMEM) project in Northern Hispaniola (PAPA No. 72051719CA00004). We extend our sincerest gratitude to Jerry Bauer (Program Director, USFS‑IITF/International Cooperation) for his guidance, notably for his commendable dedication and consistent technical support, inter‑agency managerial skill set, and global multimedia dissemination of our research and conservation education materials. We also thank Harry R. Recher for his meticulous and thoughtful review of the manuscript. We thank the editorial staff for their thoughtful and rigorous evaluation, attentive review, and steady guidance throughout the preparation and revision of this manuscript.

Literature Cited

Australian Birds. 2024. Rufous (Nankeen) Night-Heron Nycticorax caledonicus. Australian Birds database, version 2024, Australian Birds, Canberra, Australia.

Bennett, A. T. D. and M. Théry. 2007. Avian color vision and coloration: Multidisciplinary evolutionary biology. American Naturalist 169: S1-S6.

BirdLife International. 2024. Species factsheet: Nankeen Night-Heron Nycticorax caledonicus. [online]. Accessed 11 January 2025.

Britton, S. and G. Davidowitz. 2023. The adaptive role of melanin plasticity in thermally variable environments. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 36: 1811-1821.

Cano-Ortiz, A., C. M. Musarella, J. C. Piñar Fuentes, C. J. Pinto Gomes and E. Cano. 2018. Advances in the knowledge of the vegetation of Hispaniola (Caribbean Central America). Pages 1-24 in Vegetation of Central America (M. Kappelle, ed.). InTechOpen, London, U.K.

da Silva, L. G., K. Kawanishi, P. Henschel, A. Kittle, A. Sanei, A. Reebin, D. Miquelle, A. B. Stein, A. Watson, L. B. Kekule, R. B. Machado and E. Eizirik. 2017. Mapping black panthers: Macroecological modeling of melanism in leopards (Panthera pardus). PLOS ONE 12: e0170378.

del Hoyo, J., A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal (eds.). 1992. Handbook of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

Ducrest, A.‑L., L. Keller and A. Roulin. 2008. Pleiotropy in the melanocortin system: melanism correlates with behaviour, physiology and life history traits. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 23: 502-510.

Frost, P. G. H. 2013 [updated 2025]. Nankeen night heron | Umu kōtuku. In New Zealand Birds Online (C. M. Miskelly, ed.). [online]. Accessed 11 January 2025.

Guay, P. J., D. A. Potvin and R. W. Robinson. 2012. Aberrations in plumage coloration in birds. Australian Field Ornithology 29: 23-30.

Harris, R. B., K. Irwin, M. R. Jones, S. Laurent, R. D. H. Barrett, M. W. Nachman, J. M. Good, C. R. Linnen, J. D. Jensen and S. P. Pfeifer. 2019. The population genetics of crypsis in vertebrates: recent insights from mice, hares, and lizards. Heredity 123: 305-318.

Heather, B. and H. Robertson. 2015. The Field Guide to the Birds of New Zealand. Penguin Random House, Auckland, New Zealand.

Hothem, R. L., B. E. Brussee, W. E. Davis, Jr., A. Martínez-Vilalta, A. Motis and G. M. Kirwan. 2020. Black-crowned Night Heron Nycticorax nycticorax. In Birds of the World, v. 1.0. (S. M. Billerman, ed.). Cornell Lab of Ornithology Ithaca, New York, U.S.A.

Jeon, D.-J., S. Paik, S. Ji and J.-S. Yeo. 2021. Melanin-based structural coloration of birds and its biomimetic applications. Applied Microscopy 51: 1-11.

Kuleshov, Y., L. Qi, R. Fawcett and D. Jones. 2008. On tropical cyclone activity in the Southern Hemisphere: Trends and the ENSO connection. Geophysical Research Letters 35: L14S08.

Kushlan, J. A. and J. A. Hancock. 2005. The herons. Oxford University Press, Oxford, U.K.

Lepage, D. n.d. Nankeen Night Heron. Avibase: the world bird database. [online]. Accessed 5 January 2025.

López, L. I., J. M. Mora and A. A. Rivera. 2024. Color aberrations in seven bird species in Costa Rica. Ornitología Neotropical 35: 55-62.

Luo, H., S. Luo, W. Fang, Q. Lin, X. Chen and X. Zhou. 2022. Genomic insight into the nocturnal adaptation of the black-crowned night heron (Nycticorax nycticorax). BMC Genomics 23: 683.

Marchant, S. and P. J. Higgins (eds.). 1990. Nankeen night heron (Nycticorax caledonicus). Pages 625-637 in Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds, v. 1: Ratites to Ducks. Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Australia.

Martínez-Vilalta, A., A. Motis and G. M. Kirwan. 2021. Nankeen Night Heron (Nycticorax caledonicus). In Birds of the World, v. 1.0. (S. M. Billerman, ed.). Cornell Lab of Ornithology Ithaca, New York, U.S.A.

Mason, N. A. and R. C. K. Bowie. 2020. Plumage patterns: Ecological functions, evolutionary origins, and advances in quantification. Ornithology 137: 1-29.

McGraw, K. J., K. Wakamatsu, S. Ito, P. M. Nolan, P. Jouventin, F. S. Dobson, R. E. Austic, R. J. Safran, L. M. Siefferman, G. E. Hill and R. S. Parker. 2004. You can’t judge a pigment by its color: Carotenoid and melanin content of yellow and brown feathers in swallows, bluebirds, penguins, and domestic chickens. The Condor 106: 390-395.

Ng, C. S. and W.-H. Li. 2018. Genetic and molecular basis of feather diversity in birds. Genome Biology and Evolution 10: 2572-2586.

Oficina Nacional de Estadística (ONE) 2023. Tu municipio en cifras: Monte Cristi. Oficina Nacional de Estadística, Santo Domingo, República Dominicana.

Pitelka, Frank A. 1938. Melanism in the Black-crowned Night Heron. The Auk 55: 518-519.

Pratt, H. D., D. G. Bruner and D. Berrett. 1987. A field guide to the birds of Hawaii and the Tropical Pacific. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Roulin, A. 2004. The evolution, maintenance and adaptive function of genetic colour polymorphism in birds. Biological Reviews 79: 815-848.

Spendelow, J. A. and S. R. Patton. 1988. National atlas of coastal waterbird colonies in the contiguous United States, 1976-82. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Report 88. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

Sullivan, B. L., C. L. Wood, M. J. Iliff, R. E. Bonney, D. Fink and S. Kellinge. 2009. eBird: A citizen-based bird observation network in the biological sciences. Biological Conservation 142: 2282-2292.

van Grouw, H. 2013. What colour is that bird? The causes and recognition of common colour aberrations in birds. British Birds 106: 17-29.

van Grouw, H. 2017. The dark side of birds: melanism—facts and fiction. Bulletin of the British Ornithological Club 137: 12-36.

Xie, Z., Y. Du and S. Yang. 2015. Zonal extension and retraction of the subtropical westerly jet stream and evolution of precipitation over East Asia and the Western Pacific. Journal of Climate 28: 6783-6798.