Seasonal distribution of the Western Cattle Egret (Ardea ibis) in southern South America, the Falkland Islands and the Antarctic region

Abstract

The Western Cattle Egret (Ardea ibis) was confined to western Eurasia and Africa until it colonized northeastern South America in the late 19th century and quickly spread across the Western Hemisphere, arriving in southern South America by 1969. We analyzed its seasonal distribution in southern South America and adjacent regions based on 50,281 eBird records in South America south of 20° S, 77 records from the Falkland Islands, and 14 records from the Antarctic region (south of continental South America and the Falkland Islands), during 1978-2023. From 20-40° S, the proportion of records increased with latitude during austral summer and decreased during austral fall, winter, and spring. South of 40° S, egrets occurred mostly during fall, indicative of post-breeding dispersal, with the proportion of records increasing with latitude during fall and decreasing during winter, spring, and summer. A few individuals lingered during winter at the highest latitudes in southern South America, the Falkland Islands, and South Georgia Island, but there are no winter records from farther south. These patterns suggest that the southernmost populations of Western Cattle Egret in South America are partially migratory, with many individuals migrating southward during summer and fall, and returning northward before winter. Most if not all individuals dispersing over open ocean to the Falkland Islands and Antarctic islands die from predation or starvation. Further studies are needed to better document the dispersal and migratory patterns of Western Cattle Egret in southern South America.

Key words: Antarctica, Argentina, Chile, eBird, Falkland Islands, migration, Neotropical austral migrants, Neotropics.

Introduction

Four systems of bird migration occur within the Neotropics, including intra-tropical, altitudinal, austral, and longitudinal migrations (Jahn et al. 2020). Birds breeding in the temperate latitudes of South America and migrating northward during the non-breeding season are referred to as austral migrants (Chesser 1994, Hayes et al. 1994, Jahn et al. 2004, Capllonch 2018), Neotropical migrants (Hayes 1995, Joseph 1997), or Neotropical austral migrants (Cueto and Jahn 2008, Jahn et al. 2020). Despite a growing number of studies on these species in recent decades (Jahn et al. 2020), much more research is needed to better understand which species migrate, the seasonal timing of their migration, and their migratory routes and destinations in southern South America.

The Cattle Egret (Ardea ibis, formerly Bubulcus ibis) was recently reclassified as Ardea (Chesser et al. 2024, Gill et al. 2025), based mostly on genetic data (Huang et al. 2016, Hruska et al. 2023). The taxon was also recently split into two sibling species, based largely on differences in alternate plumage and geographic range (Ahmed 2011): (1) Western Cattle Egret (Ardea ibis) of western Eurasia, Africa, North America, and South America (Fig. 1); and (2) Eastern Cattle Egret (Ardea coromanda) of eastern Eurasia and Australia (Gill et al. 2025). The Western Cattle Egret first appeared in the Western Hemisphere during 1877-1882 in Guyana (Bond 1957, Palmer 1962) and subsequently spread throughout the Western Hemisphere (Sprunt 1955, Davis 1960, Blaker 1971, Crosby 1972, Handtke and Mauersberger 1977, Arendt 1988, Massa et al. 2014, Pulido Capurro et al. 2020, Miño et al. 2022). The Eastern Cattle Egret was introduced to Australia in 1933 (18 released; Serventy and Whittell 1948) and the Western Cattle Egret was introduced to Hawaii in 1959 (105 released; Breese 1959), augmenting their rate of range expansion to new regions.

In southern South America, the Western Cattle Egret was first recorded in Argentina in 1969 (Olrog 1972, Rumboll and Canevari 1975), Chile in 1969 (Post 1970), Paraguay in 1975 (Handtke and Mauersberger 1977), Uruguay in 1976 (Gore and Gepp 1978), and Tierra del Fuego near the southern tip of South America by 1975 (Venegas 1975, Venegas and Jory 1979). Nesting in southern South America was first reported in Argentina in 1972 (Narosky 1973). Individuals dispersing southeastward or southward across the open ocean were first reported from the Falkland Islands in 1976 (Strange 1979) and the Antarctic islands of South Georgia Island in 1977 (Jehl et al. 1978), South Shetland Islands in 1979 (Schlatter and Duarte 1979), South Orkney Islands in 1981 (Prince and Croxall 1983), and Argentine Islands of the Antarctic Peninsula in 1979 (Prince and Croxall 1983).

The seasonal movements of Western Cattle Egrets are highly variable, even within a population. Although some individuals are relatively sedentary, many in all four continents exhibit strong patterns of post-breeding dispersal and long-distance migration, which can be difficult to distinguish, especially for individuals breeding in temperate latitudes (Kushlan and Hancock 2005, Telfair 2023). For example, data from nestling Western Cattle Egrets banded in South Africa reveal a seasonal pattern of dispersal northward in austral winter and southward in austral summer, but some banded adults recovered during the summer in Central Africa apparently did not return to South Africa to breed, and coastal populations are more sedentary than inland populations (Siegfried 1970, Kopij 2017). Nomadism and extreme vagrancy also occur, with some individuals dispersing thousands of km from where they hatched to distant locations, including ships (which may facilitate dispersal) and remote islands (Enticott 1984, Kushlan and Hancock 2005, Marin and Caceres 2010, Telfair 2023).

In southern South America, the Western Cattle Egret is considered an austral migrant with post-breeding dispersal south of its breeding range (Kushlan and Hancock 2005, Telfair 2023). However, its seasonal patterns of distribution in southern South America have not been previously analyzed. In 2002, eBird (ebird.org) was launched as an online citizen science database that provides researchers with a vast quantity of distributional records that can be used for analyzing the seasonal distribution of birds (Sullivan et al. 2009, 2014, Wood et al. 2011). In this study, we use eBird data, augmented with a review of literature records, to document seasonal patterns in the distribution of the Western Cattle Egret in southern South America, the Falkland Islands, and the Antarctic region.

Methods

We downloaded all submitted eBird records of the Western Cattle Egret that had been vetted (approved by regional experts as volunteer reviewers) from south of 20° S in southern South America, the Falkland Islands, and to the south of these regions through 30 November 2023. A record was defined as an observation of one or more individuals at a given locality on a given date. Duplicates from shared observations were deleted. Records at sea that were closer to the Falkland Islands than the continent were classified as records for the Falkland Islands. All records south of continental South America and the Falkland Islands were classified as records for the Antarctic region.

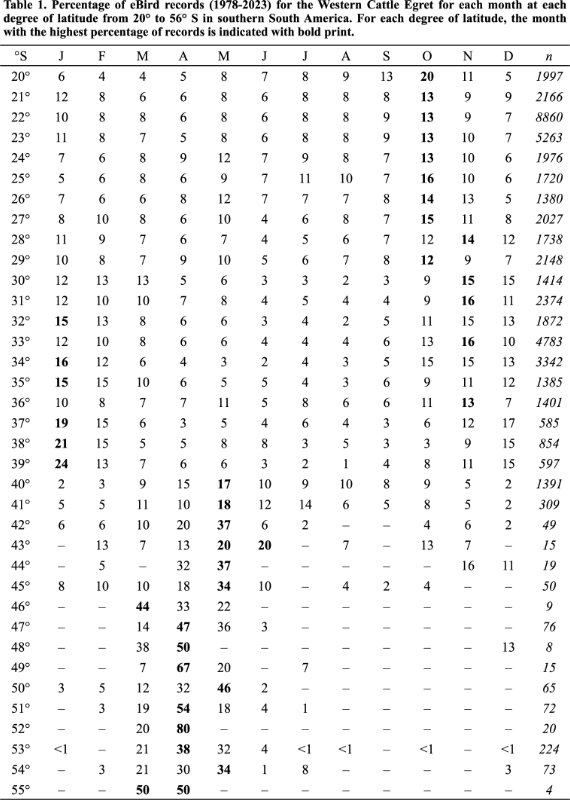

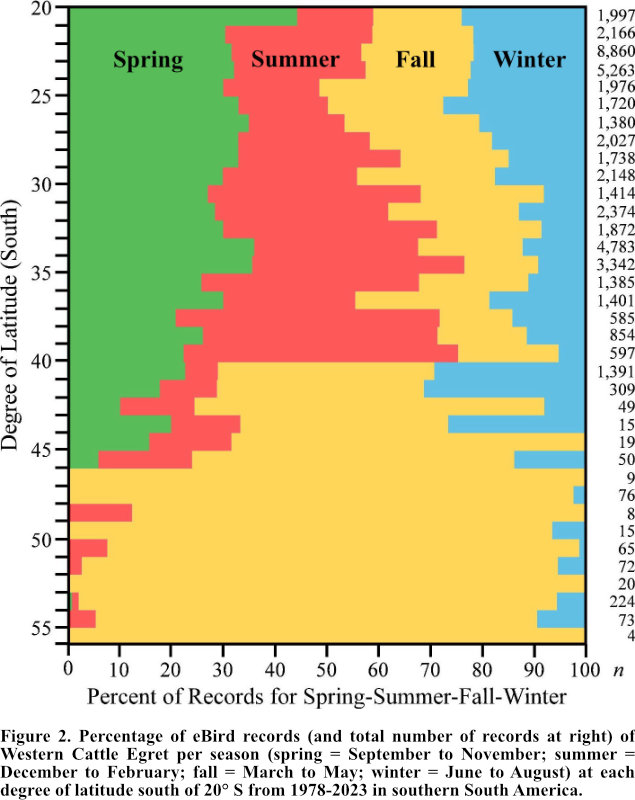

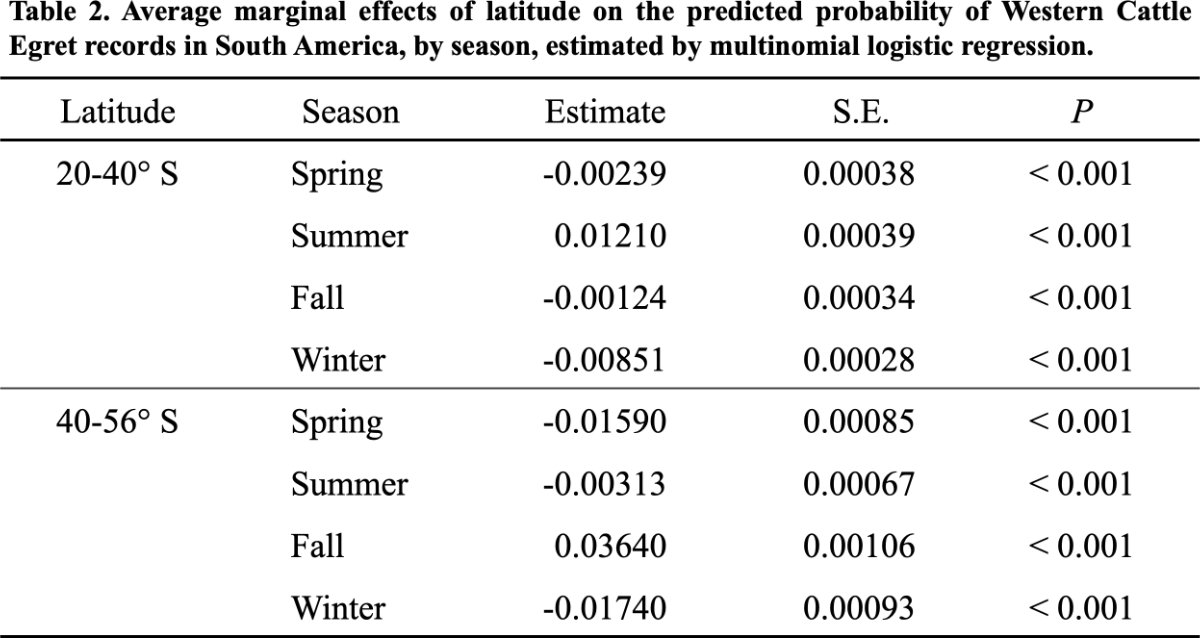

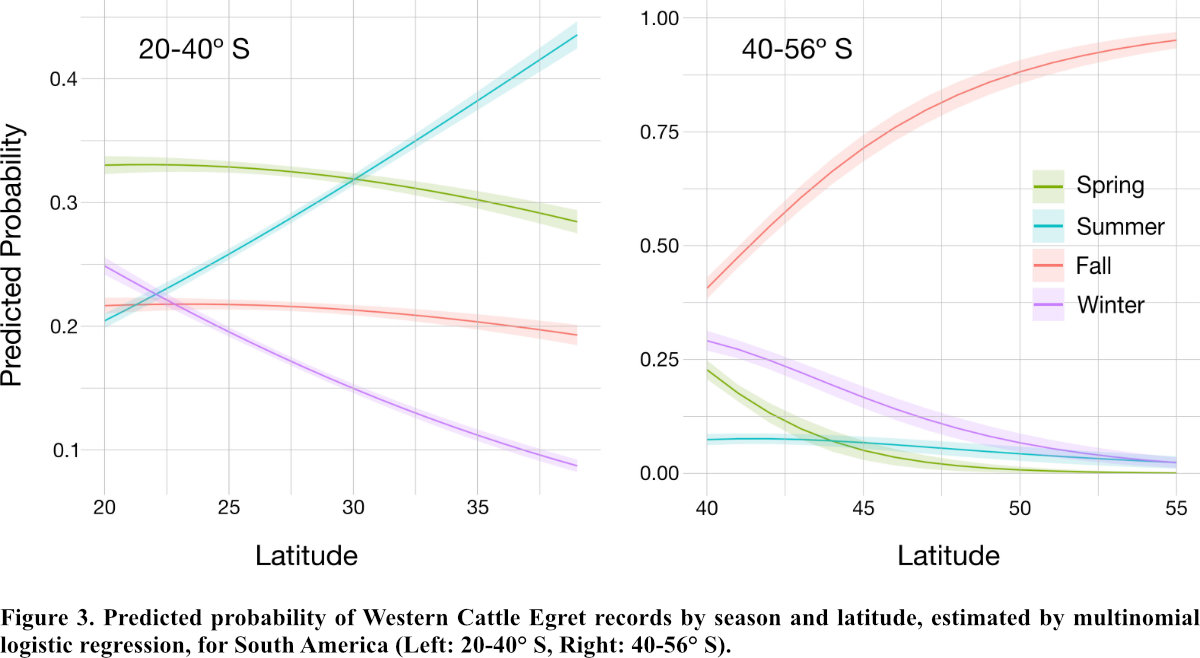

For each degree of latitude from 20-56° S in South America, we calculated the percentage of records occurring during each month and each season, defined as spring (September to November), summer (December to February), fall (March to May), and winter (June to August). To estimate how the probability that a record falls into each season varies along a latitudinal gradient, a multinomial logistic regression model was constructed, with latitude as the independent variable and season as the dependent variable, using R version 4.5.0 (R Core Team 2025) and the multinom function from the nnet package (Venables and Ripley 2002). Furthermore, based on the results from the model, the average marginal effect of the predicted probability for each season was calculated, using the avg slopes function from the marginaleffects package (Arel-Bundock et al. 2024). This value represents the average rate of change in the predicted probability per degree of latitude change. Because preliminary analyses showed a clear distinction in the trend of the seasonal proportions of records across the 40º S boundary, these analyses were performed separately for the 20-40º S and 40-56º S datasets.

The percentage of records during each season were calculated separately for the Falkland Islands and the Antarctic region, and one-sample chi-square goodness-of-fit tests (χ2 statistic; Zar 2010) were computed using an online calculator (MedCalc Software Ltd. n.d.) to test for seasonal differences in the proportions of records. An online calculator (National Hurricane Center and Central Pacific Hurricane Center n.d.) was used to measure distances between noteworthy locality records.

Results

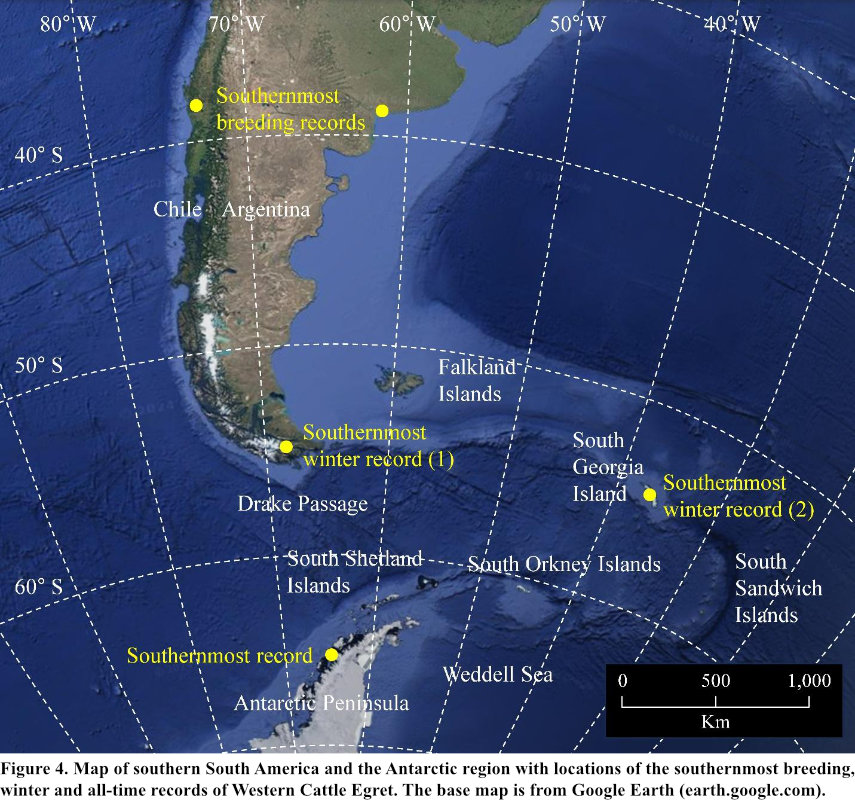

After deleting duplicates from shared observations, we obtained 50,281 eBird records of the Western Cattle Egret from the South American continent and adjacent marine areas (excluding records south of the continent) between 20° S and the southern tip of South America at 56° S, ranging from 11 March 1978 to 30 November 2023. From 20-40° S, egrets were most common during spring and summer, with a peak in monthly records occurring in October from 20-28° S, in October or November from 28-32° S, and in either November, December, or January from 32-40° S (Table 1, Fig. 2). South of 40° S, egrets occurred mostly during fall, with a peak in monthly records occurring during March, April, or May, and much fewer birds during spring, summer, and winter (Table 1, Fig. 2). Based on the multinomial logistic regression, in the 20-40º S range, the predicted probability of summer records increased by 1.21 percentage points per degree of latitude (P < 0.001), while those for spring, fall and winter decreased by 0.24, 0.12 and 0.85 points, respectively (all P < 0.001; Table 2, Fig. 3). In the 40-56º S range, fall records increased by 3.64 points (P < 0.001), while those for spring, summer, and winter decreased by 1.59, 0.31 and 1.74 points, respectively (all P < 0.001; Table 2, Fig. 3). Some individuals lingered throughout the winter even at high latitudes near the southern tip of South America; the southernmost eBird winter record was an egret photographed at Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego, Argentina (54° 49′ S, 68° 20′ W), from 30 June 2023 (Ledesma n.d.) to 28 July 2023 (Godoy n.d.) (Fig. 4).

We obtained 77 eBird records from the Falkland Islands and adjacent marine areas from 18 March 1993 to 20 April 2023. The vast majority of records occurred during fall (90%; 24 records in March, 34 in April, 11 in May), with 8% during summer (four records in January, two in February), 1% during spring (one record in November), and 1% in winter (one record in August) (χ2 = 172.30, df = 3, P < 0.001). The only winter record was from Saunders Island (51° 19′ S, 60° 14′ W) on 20 August 2013 (Bobowski n.d.).

We obtained 14 eBird records from the Antarctic region southeast or south of the South American continent and Falkland Islands, including four records from the vicinity of South Georgia Island and 10 records in the Drake Passage, South Shetland Islands, and Weddell Sea from 30 March 1986 to 19 March 2023. Most of the records occurred during fall (79%; 10 records in March, one in April), 14% during summer (two records in January), and 7% during spring (one record in November) (χ2 = 22.00, df = 3, P < 0.001). The southernmost eBird record was a flock of 14 extremely emaciated birds attracted to the lights of a ship at night in the northwestern Weddell Sea, 268 km E of Joinville Island at the northeastern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula (63° 11′ S, 49° 41′ W), on 30 March 1986 (Wallace n.d.).

Discussion

In southern South America, the Western Cattle Egret was first recorded nesting at Laguna de Burgos, Buenos Aires, Argentina (36° 36′ S, 59° 59′ W), on 11 December 1972 (Narosky 1973). It subsequently established nesting colonies throughout northern and central Argentina, with incubation occurring from November to March and nestlings from December to April (De la Peña and Montalti 2014). Despite the rapid rate of new records occurring much farther south in Tierra del Fuego and the Antarctic region in the 1970s (see Introduction above), the southernmost nesting colony, first detected in October 1989, is at Laguna Sauce Grande (38° 56′ S, 61° 23′ W; Padín and Néstor 1996), only 287 km south of where it was first found nesting in 1972 (Narosky 1973) (Fig. 4). In Chile, the southernmost nesting colony is at a similar latitude at Labranza, Araucanía (38° 46′ S, 72° 45′ W), where nesting was reported on 4 January 2020 (Raimilla n.d.) (Fig. 4). The Western Cattle Egret does not appear to be expanding its breeding range southward during the last few decades in response to climate change, in contrast with many other birds in the region (Capllonch et al. 2020), and despite an increase in exploration of more southerly locations.

Our analyses demonstrate a strong pattern of post-breeding southward dispersal by the Western Cattle Egret in southern South America, beginning during summer at 20-40° and continuing during fall, especially south of 40° S, as the proportion of fall records increases and the proportions of winter, spring, and summer records decrease with latitude. Because there are no published studies of band recoveries or satellite telemetry of the Western Cattle Egret in southern South America, the fate of most individual birds that disperse southward after the breeding season is poorly known. Given the paucity of winter records at higher latitudes in continental South America, with some lingering year-round as far south as the southern tip of South America, most southward dispersing birds presumably migrate northward before the onset of winter and return to nesting colonies during the following breeding season. These patterns suggest that the Western Cattle Egret is a partial migrant in southern South America, with a portion of the population migrating southward during summer and fall, and returning northward before winter.

Remarkably, but consistent with their explosive colonization of the rest of the world, some Western Cattle Egrets disperse southeastward or southward across hundreds or thousands of km of open ocean, usually in fall but sometimes during spring or summer, to the Falkland Islands, South Georgia Island, South Sandwich Islands, South Orkney Islands, South Shetland Islands, and Argentine Islands (Jehl et al. 1978, Schlatter and Duarte 1979, Strange 1979, Prince and Croxall 1983, 1996, Clark 1985, Torres et al. 1986, Trivelpiece et al. 1987, Kaiser et al. 1988, Rootes 1988, Lange and Naumann 1990, Mönke and Bick 1990, Aguirre 1995, Orgeira 1995, 1996, Silva et al. 1995, Lumpe and Weidinger 2000, Ibáñez et al. 1999/2001, Kampp 2001, Peter et al. 2008, Coria et al. 2011, Petersen et al. 2015, Braun et al. 2023, Trokhymets et al. 2024). Irruptions sometimes occur, with at least 5,000 individuals arriving in the Falkland Islands from mid-March to mid-May 1986 (Douse 1986) and at least 50 individuals on South Georgia Island in 1979 and 1986 (Prince and Croxall 1996). The southernmost published record is a dead bird found at Black Island, in the Argentine Islands just west of the Antarctic Peninsula (65° 15′ 31″ S, 64° 16′ 51″ W; Fig. 4), in early April 2013 (Trokhymets et al. 2024), and there are several records < 5 km to the north at Galindez Island, also in the Argentine Islands, in December 1979 (Prince and Croxall 1983), late March and early April 2013, and April 2019 (Trokhymets et al. 2024). These locations are at least 2,930 km S of the nearest known nesting colony (Fig. 4). It is unknown whether any of these birds ever return to the South American continent. Post-breeding dispersal to such inhospitable localities represents normal exploratory behavior rather than an act of desperation or navigational error (Lees and Gilroy 2021, Veit 2022), even though it appears to be a suicidal one-way journey for most if not all individuals. Many are emaciated when they arrive on boats or islands, and are either preyed upon by avian predators or starve to death. Few remain alive by winter, with records from June, July, and August in the Falkland Islands (Strange 1979, Bobowski n.d.) and June on South Georgia Island, with a similar latitude (54-55° S, precise locality not given; Prince and Croxall 1996) as the southernmost winter record in continental South America (details cited in Results above) (Fig. 4).

In North America, the Western Cattle Egret breeds at much higher latitudes than in South America, with the northernmost at Middle Quill Lake, Saskatchewan, Canada (51° 56′ N, 104° 13′ W; Beyersbergen 2008). However, it does not disperse as far toward higher latitudes, with the northernmost eBird record in continental North America near Fort Simpson, Northwest Territories, Canada (61° 55′ N, 121° 35′ W), on 26 October 2011 (Larter n.d.). In western Eurasia, it breeds at even higher latitudes, as far north as the Burton Mere Wetlands, Wales, UK (53° 15′ N, 03° 02′ W; Rare Bird Alert 2017, Eaton 2022), and it disperses farther northward, with the northernmost eBird record from Kløkstad, Nordland, Norway (67° 23′ N, 14° 36′ E), on 29 September 2014 (Birkelund n.d.).

In contrast with the Western Cattle Egret, the Eastern Cattle Egret does not disperse as far toward the poles. Its northernmost record was a dead individual found at Agattu, Aleutian Islands, Alaska, USA (52° 25′ N, 173° 36′ E), on 19 June 1988 (Gibson and Kessel 1992, Alaska Historical Data n.d.), and its southernmost record is from Green Gorge, Macquarie Island, Australia (54° 37′ 53.0″ S, 158° 53′ 56.1″ E), on 3 April 2018 and found dead the following day (Bird n.d.).

Further studies of Western Cattle Egrets that are banded, tagged with light-level geolocators, or outfitted with satellite transmitters are needed to better document the dispersal and migratory trajectories of individuals and populations in southern South America.

Acknowledgments

We thank the contributors of eBird for posting records on eBird and the editors and administrators for curating the records. And we thank José Ramírez-Garofalo, Richard Reed Veit, and Alberto Yanosky for reviewing the manuscript.

Literature Cited

Aguirre, C. A. 1995. Distribution and abundance of birds at Potter Peninsula, 25 de Mayo (King George) Island, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. Marine Ornithology 23: 23-31.

Ahmed, R. 2011. Subspecific identification and status of Cattle Egret. Dutch Birding 33: 294-304.

Alaska Historical Data. n.d. eBird Checklist: S187579022. eBird, Ithaca, New York, U.S.A. [online]. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Arel-Bundock V, N. Greifer and A. Heiss. 2024. How to interpret statistical models using marginaleffects for R and Python. Journal of Statistical Software 111: 1-32. [online].

Arendt, W. J. 1988. Range expansion of the Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis) in the greater Caribbean basin. Colonial Waterbirds 11: 252-262.

Beyersbergen, G. W. 2008. Cattle Egrets and nests found during Franklin’s Gull surveys in Saskatchewan in 2006 and 2007. Blue Jay 66: 70-73.

Bird, J. n.d. eBird Checklist: S44772178. eBird, Ithaca, New York, U.S.A. [online]. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Birkelund, R. n.d. eBird Checklist: S61119662. eBird, Ithaca, New York, U.S.A. [online]. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Blaker, D. 1971. Range expansion of the Cattle Egret. Ostrich 42(sup 1): 27-30.

Bobowski, M. n.d. eBird Checklist: S46679721. eBird, Ithaca, New York, U.S.A. [online]. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Bond, J. 1957. Second supplement to the check-list of birds of the West Indies (1956). Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.

Braun, C., H. Grämer and H.-U. Peter. 2023. Records of vagrant and visitor bird species in the Fildes Region, King George Island, Maritime Antarctic, between 1980 and 2023. Ukrainian Antarctic Journal 21: 210-229.

Breese, P. 1959. Information on Cattle Egret, a bird new to Hawaii. ʻElepaio 20:33-34.

Capllonch, P. 2018. Un panorama de las migraciones de aves en Argentina. Hornero 33: 1-18.

Capllonch, P., F. E. Hayes and F. D. Ortiz. 2020. Escape al sur: Una revisión de las aves que expandieron recientemente su rango de distribución en Argentina. Hornero 35: 111-126.

Chesser, R. T. 1994. Migration in South America, an overview of the austral system. Bird Conservation International 4: 91-107.

Chesser, R. T., S. M. Billerman, K. J. Burns, C. Cicero, J. L. Dunn, B. E. Hernández-Baños, R. A. Jiménez, O. Johnson, A. W. Kratter, N. A. Mason, P. C. Rasmussen and J. V. Remsen, Jr. 2024. Sixty-fifth supplement to the American Ornithological Society’s Check-list of North American Birds. Ornithology 141: 1-21.

Clark, G. S. 1985. Cattle Egrets near Antarctica in April. Notornis 32: 325.

Coria, N.R., D. Montalti, E. F. Rombola, M. M. Santos, M. I. García Betoño and M. A. Juares. 2011. Birds at Laurie Island, South Orkney Islands, Antarctica: breeding species and their distribution. Marine Ornithology 39: 207-213.

Crosby, G. T. 1972. Spread of the Cattle Egret in the Western Hemisphere. Bird-Banding 43: 205-212.

Cueto, V. R. and A. E. Jahn. 2008. Sobre la necesidad de tener un nombre estandarizado para las aves que migran dentro de América del Sur. Hornero 23: 1-4.

Davis, D. E. 1960. The spread of the Cattle Egret in the United States. Auk 77: 421-424.

De la Peña, M. and D. Montalti. 2014. Nidificación de las aves argentinas. Comunicaciones del Museo Provincial de Ciencias Naturales “Florentino Ameghino” (nueva serie) 18: 1-136.

Douse, A. 1986. The 1986 Cattle Egret ‘invasion’. Warrah Annual Report 1986: 10.

Eaton, M. A. 2022. Rare breeding birds in the UK in 2020. British Birds 115: 623-686.

Enticott, J. W. 1984. New and rarely recorded birds at Gough Island, March 1982 – December 1983. Cormorant 12: 75-81.

Gibson, D. D. and B. Kessel. 1992. Seventy-four new avian taxa documented in Alaska 1976-1991. Condor 94: 454-467.

Gill, F., D. Donsker and P. Rasmussen (eds.). 2025. IOC World Bird List (v15.1). [online]. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Godoy, S. n.d. eBird Checklist: S145827480. eBird, Ithaca, New York, U.S.A. [online]. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Gore, M. E. J. and A. R. M. Gepp. 1978. Las Aves del Uruguay. Mosca Hnos. S.A., Montevideo, Uruguay.

Handtke, K. and G. Mauersberger. 1977. Die Ausbreitung des Kuhreihers, Bubulcus ibis (L.). Mitteilungen aus dem Zoologischen Museum in Berlin 53, Annalen für Ornithologie 1: 1-78.

Hayes, F. E. 1995. Definitions for migrant birds: what is a Neotropical migrant? Auk 112: 521-523.

Hayes, F. E., P. A. Scharf and R. S. Ridgely. 1994. Austral bird migrants in Paraguay. Condor 96: 83-97.

Hruska, J. P., J. Holmes, C. Oliveros, S. Shakya, P. Lavretsky, K. G. McCracken, F. H. Sheldon and R. G. Moyle. 2023. Ultraconserved elements resolve the phylogeny and corroborate patterns of molecular rate variation in herons (Aves: Ardeidae). Ornithology 140: ukad005. [online].

Huang, Z. H., M. F. Li and J. W. Qin. 2016. DNA barcoding and phylogenetic relationships of Ardeidae (Aves: Ciconiiformes). Genetics and Molecular Research 15: gmr.15038270. [online].

Ibáñez, F. J., F. de Angulo and J. J. Monge Minguillón. 1999/2001. Avifauna de la Isla Decepción. Archipiélago de las Shetland del Sur. Antártida. Anuario Ornitológico Doñana 1: 163-169.

Jahn, A. E., D. J. Levey and K. G. Smith. 2004. Reflections across hemispheres: a system-wide approach to New World bird migration. Auk: Ornithological Advances 121: 1005-1013.

Jahn, A. E., V. R. Cueto, C. S. Fontana, A. C. Guaraldo, D. J. Levey, P. P. Marra and T. B. Ryder. 2020. Bird migration within the Neotropics. Auk 137: 1-23.

Jehl, J. R. Jr., F. S. Todd, M. A. E. Rumboll and D. Schwartz. 1978. Notes on the avifauna of South Georgia. Gerfaut 68: 534-550.

Joseph, L. 1997. Towards a broader view of Neotropical migrants: consequences of a re-examination of austral migration. Ornitología Neotropical 8: 31-36.

Kaiser, M., H-U. Peter and A. Gebauer. 1988. Kuhreiher, Ardeola ibis (L.), in der Antarktis. Beiträge zur Vogelkunde 34: 202-203.

Kampp, K. 2001. Seabird observations from the south and central Atlantic Ocean, Antarctica to 30°N, March-April 1998 and 2000. Atlantic Seabirds 3: 1-14.

Kopij, J. 2017. Migratory connectivity of South African Cattle Egrets (Bubulcus ibis, Ciconiiformes, Ardeidae). Zoologicheskii Zhurnal 96: 418-428.

Kushlan, J. A. and J. A. Hancock. 2005. Herons. Oxford University Press, Oxford, U.K.

Lange, U. and Naumann, J. 1990. Weitere Erstnachweise von Vogelarten im Südwesten von King George Island (Südshetland-Inseln, Antarktis). Beiträge zur Vogelkunde 36: 165-170.

Larter, N. n.d. eBird Checklist: S16828209. eBird, Ithaca, New York, U.S.A. [online]. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Ledesma, M. I. n.d. eBird Checklist: S143169405. eBird, Ithaca, New York, U.S.A. [online]. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Lees, A. and J. Gilroy. 1921. Vagrancy in Birds. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.A.

Lumpe, P. and K. Weidinger. 2000. Distribution, numbers and breeding of birds at the northern ice-free areas of Nelson Island, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica, 1990-1992. Marine Ornithology 28: 41-46.

Marin, M. and P. Caceres. 2010. Sobre las aves de la isla de Pascua. Boletín del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Chile. 59: 75-95.

Massa, C., M. Doyle and R. C. Fortunato. 2014. On how Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis) spread to the Americas: meteorological tools to assess probable colonization trajectories. International Journal of Biometeorology 58: 1879-1891.

MedCalc Software Ltd. n.d. One-way chi-squared test. [online]. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Miño, C. I., C. T. Geronimo, C. C. Castillo, I. A. S. Bonatelli, T. A. Valdes, B. A. Laroca and S. N. del Lama. 2022. Genetic insights into the range expansion of the Cattle Egret (Pelecaniformes: Ardeidae) in Brazil and population differentiation between the native and colonized areas. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 136: 306-320.

Mönke, R. and A. Bick. 1990. Verkommen des Kuhreihers, Bubulcus ibis (L.), in der Antarktis. Records of the Cattle Egret, Bubulcus ibis (L.), in the Antarctic. Mitteilungen aus dem Zoologischen Museum in Berlin, Supplementheft Annalen für Ornithologie 14, 66: 69-79.

Narosky, S. 1973. Primeros nidos de la Garcita Buyera en la Argentina (Bubulcus ibis). Hornero 11: 225-226.

National Hurricane Center and Central Pacific Hurricane Center. n.d. Latitude/Longitude Distance Calculator. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. [online]. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Olrog, C. C. 1972. Adiciones a la avifauna argentina (1° suplemento de “la lista y distribución de las aves argentinas”, Opera Lilloana, IX, 1963). Acta Zoologica Lilloana 26: 255-266.

Orgeira, J. L. 1995. Presencia de Garcita bueyera (Bubulcus ibis) en el Océano Atlántico Sur, otoño de 1993. Hornero 14: 53-54.

Orgeira, J. L. 1996. Cattle Egrets Bubulcus ibis at sea in the South Atlantic Ocean. Marine Ornithology 24: 57-58.

Padín, O. H. and R. I. Néstor. 1996. Ecología energética de una colonia de nidificación de Garcita Bueyera Bubulcus ibis, en la Laguna Sauce Grande (Prov. Buenos Aires). Page 40 in IX Reunión Argentina de Ornitología Libro de Resumenes (R. Fraga, J. C. Reboreda, S. Krapovickas and A. Bosso, eds.). Asociación Ornitológica del Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Palmer, R. S. (ed.). 1962. Handbook of North American Birds. Volume 1. Loons Through Flamingos. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, U.S.A.

Peter, H-U., C. B. Büßer, O. Mustafa and S. Pfeiffer. 2008. Vögel der Antarktis–Ökologische Langzeitstudien auf der Fildes Halbinsel (King George Island). Pages 143-156 in Polarforschung–Reisen und Forschungsarbeiten deutscher Wissenschaftler in den Polargebieten (H. Benke, ed.). Meer und Museum, vol. 20, Schriftenreihe des Deutschen Meeresmuseum, Stralsund, Germany.

Petersen, E. de S., L. C. Rossi and M. V. Petry. 2015. Records of vagrant bird species in Antarctica: new observations. Marine Biodiversity Records 8: e61. [online].

Post, P. W. 1970. First report of Cattle Egret in Chile and range extensions in Peru. Auk 87: 361.

Prince, P. A. and J. P. Croxall. 1983. Birds of South Georgia: new records and re-evaluation of status. British Antarctic Survey Bulletin 59: 15-27.

Prince, P. A. and J. P. Croxall. 1996. The birds of South Georgia. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 116: 81-104.

Pulido Capurro, V., E. Olivera Carhuaz, D. Cano Coa and J. A. Flores. 2020. A 143 años de la migración de la Garza Bueyera Bubulcus ibis (Linnaeus, 1758) desde África hacia los Andes. Revista de Investigaciones Altoandinas – Journal of High Andean Research 22: 352-361.

R Core Team. 2025. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

Raimilla, V. n.d. eBird Checklist: S62996983. eBird, Ithaca, New York, U.S.A. [online]. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Rare Bird Alert. 2017. Cattle Egrets breeding in Cheshire. [online]. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Rootes, D. M. 1988. The status of birds at Signy Island, South Orkney Islands. British Antarctic Survey Bulletin 80: 87-119.

Rumboll, M. A. E. and P. J. Canevari. 1975. Invasión de Bubulcus ibis en la Argentina (Aves, Ardeidae). Neotropica 21: 162-165.

Schlatter, R. P. and W. E. Duarte. 1979. Nuevos registros ornitológicas en las Antarctica Chilena. Serie Científica Instituto Antárctica Chileno 25: 45-48.

Serventy, D. L. and H. M. Whittell. 1948. A Handbook of the Birds of Western Australia (with the Exception of the Kimberley Division). Patersons Press, Perth, Australia.

Siegfried, W. R. 1970. Mortality and dispersal of ringed Cattle Egrets. Ostrich 41: 122-135.

Silva, M. P., N. R. Coria, M. Favero and R. J. Casaux. 1995. New records of Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis, Blacknecked Swan Cygnus melancorhuphus and Whiterumped Sandpiper Calidris fuscicollis from the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. Marine Ornithology 23: 65-66.

Sprunt, A., Jr. 1955. The spread of the Cattle Egret (with particular reference to North America). Pages 259-276 in Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, Publication 4190 (anonymous, ed.). Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

Strange, I. J. 1979. Distribution of Cattle Egrets Bubulcus ibis to the Falklands Islands. Gerfaut 69: 397-401.

Sullivan, B. L., C. L. Wood, M. J. Iliff, R. E. Bonney, D. Fink and S. Kelling. 2009. eBird: a citizen-based bird observation network in the biological sciences. Biological Conservation 142: 2282-2292.

Sullivan, B. L., J. L. Aycrigg, J. H. Barry, R. E. Bonney, N. Bruns, C. B. Cooper, T. Damoulas, A. A. Dhondt, T. Dietterich, A. Farnsworth, D. Fink, J. W. Fitzpatrick, T. Fredericks, J. Gerbracht, C. Gomes, W. M. Hochachka, M. J. Iliff, C. Lagoze, F. A. La Sorte, M. Merrifield, W. Morris, T. B. Phillips, M. Reynolds, A. D. Rodewald, K. Y. Rosenberg, N. M. Trautmann, A. Wiggins, D. W. Winkler, W. K. Wong, C. L. Wood, J. Yu and S. Kelling. 2014. The eBird enterprise: an integrated approach to development and application of citizen science. Biological Conservation 169: 31-40.

Telfair, R. C. II. 2023. Western Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, B. K. Keeney, S. M. Billerman, and M. A. Bridwell, eds.). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. [online].

Torres, D., M. Gajardo and J. Valencia. 1986. Notas sobre Bubulcus ibis y Eudyptes chrysolophus de las islas Shetland del Sur. Serie Científica Instituto Antártico Chileno 34: 73-79.

Trivelpiece, S. G., G. R. Geupel, J. Kjelmyr, A. Myrcha, J. Sicinski, W. Z. Trivelpiece and N. J. Volkman. 1987. Rare bird sightings from Admiralty Bay, King George Island, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica, 1976-1987. Cormorant 15: 59-66.

Trokhymets, V., M. Veselskyi, P. Khoyetskyy, I. Shydlovskyy and I. Dykyy. 2024. New records of the Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis) from Antarctica. Waterbirds 47: 1-5.

Veit, R. R., L. L. Manne1, L. C. Zawadzki, M. A, Alamo and R. W. Henry III. 2022. Editorial: Vagrancy, exploratory behavior and colonization by birds: Escape from extinction? Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 10: 960841.

Venables, W. N. and B. D. Ripley. 2002. Modern applied statistics with S. fourth edition. Springer, New York. U.S.A.

Venegas, C. 1975. Dos adiciones a la fauna avial magallánica: Bubulcus ibis (Ardeidae) y gelaius thilius (Icteridae). Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia, Punta Arenas 13: 189-206.

Venegas, C. and J. Jory H. 1979. Guía de Campo para las Aves de Magallanes. Publicaciones del Instituto Patagonia, Punta Arenas, Chile.

Wallece, G. n.d. eBird Checklist: S49529855. eBird, Ithaca, New York, U.S.A. [online]. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Wood, C., B. Sullivan, M. Iliff, D. Fink and S. Kelling. 2011. eBird: engaging birders in science and conservation. PLoS Biology 9: e1001220. [online].

Zar, J. H. 2010. Biostatistical Analysis. 5th edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, U.S.A.