Black Heron

Egretta ardesiaca (Wagler)

Ardea ardesiaca Wagler, 1827. Syst. Av. Ardea No. 20: Senegambia.

Other names: Garceta Azabache in Spanish; Aigrette ardoisée in French; Glockenreiher in German.

Description

The Black Heron is a medium, all-black plumaged African heron with yellow feet, usually seen actively feeding in open shallow water.

Adult: This heron is all dark black save its yellow iris and feet. Roosting or standing it has a rather thick, dumpy appearance relative to other Egretta. The crown has a bushy crest, the luxuriant shaggy lanceolate plumes having a bluish tinge. During courtship, feet turn bright red, but the legs and other soft-parts colors do not change.

Variation: The sexes are alike and no geographic variation has been reported.

Juvenile: Juveniles are black like the adult, but they lack plumes.

Chick: Chick covered with dark grey down, with a notable downy white crest (Milstein and Hunter 1974). Skin, legs are green yellow. Feet are yellow.

Voice: The Black Heron tends to be silent. A low clucking sound has been reported in courtship

Weights and measurements: Length: 42-66 cm. Weight: 270-390 g.

Field characters

The Black Heron is identified by its all black plumage and yellow feet and also by its unique feeding behavior and by its distinctive posture for an egret. It often retracted its short neck so that its bushy head is close to its shoulders, making it look rather dumpy as opposed to a sleek egret (Beel 1993). In addition to its posture, it is distinguished from the Slaty Egret by being darker, having black rather than distinctively colored throat, bill, or lores. It is distinguished from the Rufous Bellied Heron and Slaty Egret by its black legs and yellow feet. It is distinguished from the dark phase of the Little Egret by being smaller and darker, with black rather than colored lores. In flight, medium dark egrets with yellow feet may look very similar.

Systematics

This is a specialized Egretta, well adapted to its peculiar feeding behavior. For example its flight feathers are particularly broad and its plumes also are shaped to help complete the closed canopy. Its distinctively colored feet are similar to other egrets, but interestingly unlike the other species, the Black Heron’s legs do not change color in the breeding season, suggesting that dark legs are important in the functioning of the Canopy behavior.

Range and status

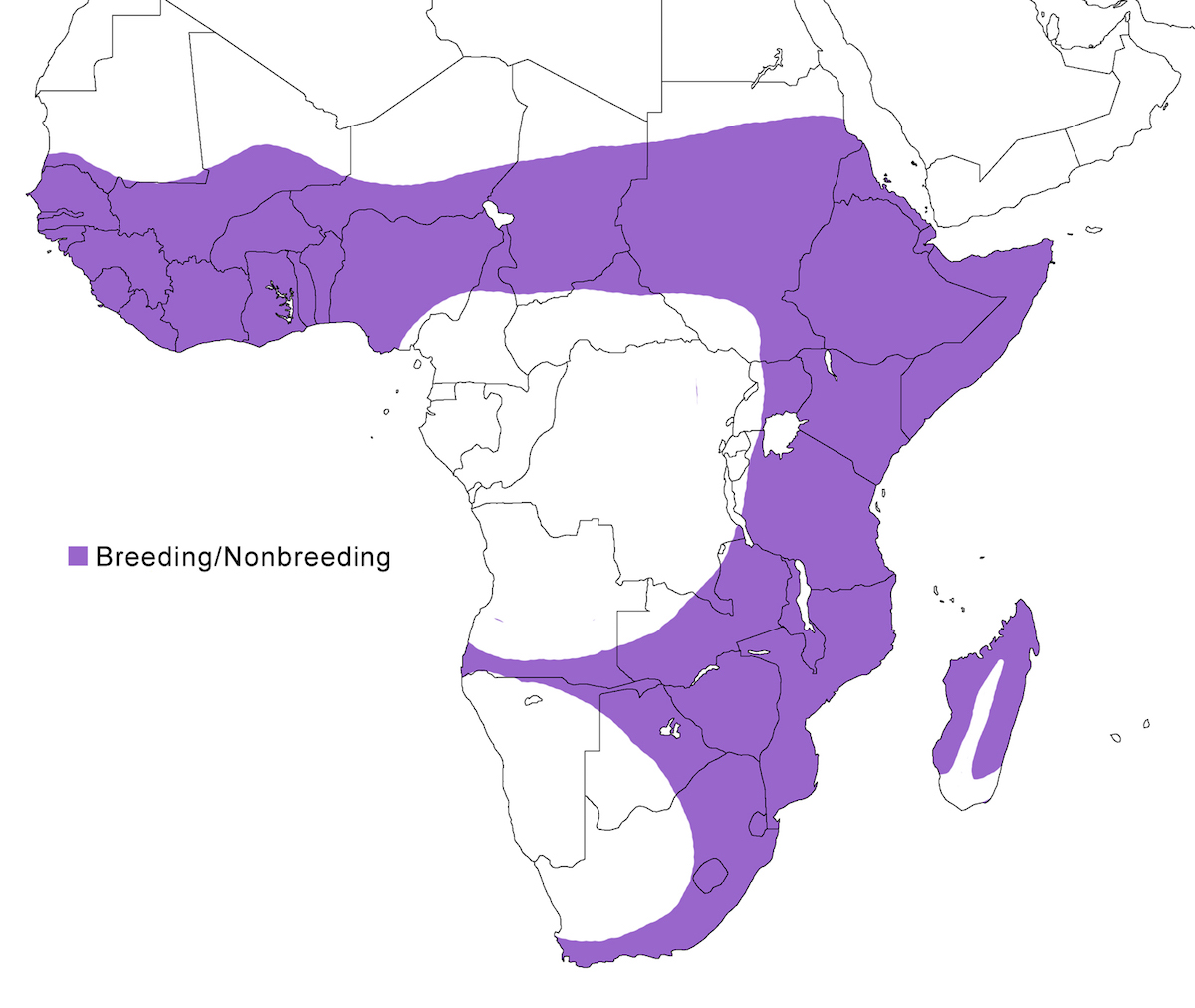

The Black Egret occurs in Africa and Madagascar.

Breeding range: It is patchily distributed in Africa south of the Sahara except forests and deserts and also breeds in Madagascar. Much remains to be known about the details of the breeding range of this species.

Migration: The migratory situation in the species is unclear. Although long considered to be primarily a residential species, it may be better considered to be a species that readily shifts areas in a search for seasonally available shallow water sites with the right feeding conditions (Hancock 1999). The heron occurs in some places year round, but local and longer migrations in response to the rainfall cycle are just as typical. It is, for example, absent from Sierra Leone and the Zimbabwe plateau in some seasons and large numbers migrate in large flocks into Tanzania from Kenya and also through The Gambia (Hancock 1999). Dry conditions desiccate some habitats and seasonal rains create temporary shallow-water feeding areas in other places, apparently inspiring these population shifts.

As a result of these movements, dispersion records occur, including in Gabon and Namibia (Von Ludwiger and Brand 2000) on the west and Egypt (Aswan) and Yemen on the east (Al-Saghier and Porter 1997).

Status: Black Heron populations are generally small, tens to hundreds, where found throughout its range (Turner 2000). However it is abundant locally at certain locations and seasons. It is best known in east Africa, where 5,000-7,000 are estimated in Tanzania (Baker and Baker in prep.). There is no sign of decreases in this area despite expanding human population pressure. The population in west Africa is also large. A remarkable 10,000-20,000 birds were reported from Guinea-Bissau in 1983, but this number of birds requires confirmation (Turner 2000). The population in Madagascar has decreased hugely in the past half century, colonies now numbering in 40-50 pair range (Langrand 1990). Recent censuses are frightening, the counted Madagascar population decreasing rapidly from 2,000 in 1992 to 250 in 1997 (Turner 2000).

Habitat

The Black Heron prefers shallow open waters, especially margins of fresh water lakes and ponds. Inland it also uses marshes, river edges, rice fields, and seasonally flooded grasslands. Along the coast it feeds along tidal rivers and creeks, mangroves, alkaline lakes, and tidal flats. It occurs from sea level to 1,500 m in Madagascar.

Foraging

The most distinctive characteristic of this species is its Canopy Feeding in which it feeds by spreading its wings over its head in a full umbrella with primaries touching the water and the erected nape plumes completing the canopy. The heron Walks Slowly or Walks Quickly to a location where it sees a fish or an otherwise appropriate spot. It then takes one or two steps, starting the formation of its Canopy, which is timed to reach completion above the potential prey. If the sequence is interrupted, the partially raised wings are immediately retracted. Otherwise, it completes the canopy and looks under it for 2-3 seconds, often Foot Stirring, and stabs at fish, presumably those incited to movement by the disturbance caused by the heron (Vandewalle 1985). After the canopy, the heron moves on a few steps to form another one, usually within a few more seconds. The heron frequently pauses to shake itself off, probably to get feathers back into position.

The functioning of this behavior has been argued for some time. While the canopy reduces reflection, provides better visibility, and obscures the silhouette of the heron, there is little evidence that these are primary functions for so complex a behavior. Whether fish are attracted to or flee the canopy and foot stirring is still debatable. There is no reason why both situations could not occur.

Some resident Black Herons feed solitarily, having habitual, well-defended feeding territories. Others feed in aggregations of a few to about 50 individuals, with a flock of up to 250 being seen in Madagascar. In these close groups, herons may tolerate the close approach of other species. A spoonbill (Platalea alba) is reported to have stabbed its bill under the canopy, without protest from the heron (Duncanson and Paxton 1994). However an ibis (Plegadis) was driven away when approaching too near (Hartmann 1995). In aggregations, Black Herons use Leap Frog Feeding to keep ahead of the moving canopy-forming group. They feed by day and especially around dusk. On the coast, they move to communal roost on high tides. They also roost communally at night.

Fish is the principal prey of the Black Heron. Aquatic insects and crustaceans are also taken.

Breeding

The Black Heron breeds at the start of the rainy season, when shallow feeding sites develop. The actual timing differs, November–January in South Africa, February–June in Madagascar, March–June in east Africa, July–August in west Africa.

The Black Heron nests in trees over water. It can also nest on bushes and in reed beds. It nests in single and mixed species colonies of herons, ibis, and cormorants. Typically there are 50-100 Black Heron nests in a colony. However in Africa, a few nests may occur within a larger colony or it may form huge colonies, for example a colony of 10,000 pairs of Black Herons was reported from Madagascar from 1950. The nest is a solid structure of twigs in tree nests, placed 1-6 m above water. They are usually well hidden in foliage of the nesting tree. The courtship behavior has not been recorded.

The eggs are dark blue, averaging 44 x 33 mm. The clutch is 2-4 eggs. Little is known about the breeding biology of this species.

Population dynamics

The population biology of this species is unknown.

Conservation

The greatest threats in Africa are human disturbance and avian predation at nest sites, and threats to the aquatic habitats on which the Black Heron depends. Human disturbance of previously large Black Heron colonies may have led to its nesting in smaller numbers in mixed colonies (Hancock 1999). The situation is complex in that it is found feeding in areas of heavy human use but is absent from areas that would seem to be prime habitat (N. Baker and E. Baker in prep.). Protection of nest sites is essential, especially through involvement with local people. Degradation of feeding habitat may restrict population size or recovery (e.g. Skinner et al. 1987). In Madagascar, human interference and habitat change have led to massive population reductions. The Black Heron population on Madagascar should be considered as globally threatened. Immediate development of an action plan for the Black Heron in Madagascar is called for.

Research needs

The feeding biology of this species is well known, but no information is available on its basic breeding biology and/or its demography.

Overview

This is a specialized Egretta, adapted to a peculiar feeding behaviour making use of its wings to form a canopy. For example, its flight feathers are particularly broad and shaped to help form the closed canopy. The plumes also help complete the canopy. Its distinctively coloured feet are similar to other egrets, but interestingly, unlike many other species, the Black Heron’s legs do not change colour in the breeding season, suggesting that dark legs are important in the functioning of the Canopy behaviour. Feeding alone, in small flocks, and even large aggregations, the ability of the species to adequately catch fish in shallow open water using its unique shadowcasting behaviour is just short of amazing. It may be in more mobile species than previously appreciated.