Little Bittern

Ixobrychus minutus (Linnaeus)

Ardea minuta Linnaeus, 1766, Syst. Nat. ed. 12, p. 240: ‘Helvetia, Aleppo’, restricted type locality, Switzerland.

Subspecies: Ixobrychus minutus podiceps (Bonaparte), 1855: Madagascar; Ixobrychus minutus payesii (Hartlaub), 1858: Casamanse, Senegal; Ixobrychus minutus novaezelandiae (Potts), 1871: Westland, South Island, New Zealand; Ixobrychus minutus dubius Mathews, 1912: Hermann’s Lake, South West Australia.

Other names: Minute Bittern, Leech Bittern, New Zealand Bittern, Australian Bittern, Black-backed Least Bittern in English; Vetorillo Común in Spanish; Blongios nain in French; Zwergdommel in German; Woudaapje in Dutch; Волчок in Russian; Xiao weijan in Chinese.

Description

The Little Bittern is a small heron with a dark back and cap and buff white neck and wing patches.

Adult: The male has a green black crown with elongated feathers forming a modest crest. The bill is yellow or yellow green with dark brown upper edge. Irises are yellow, and the lores are yellow or green. The side of the face is grey washed with a vinaceous tinge. The chin and throat are white with buff center. The back and tail is green black. The flight feathers are green black, which contrast on the upper wing with buff white wing patches. Sides of the upper breast have small tufts of elongated black feathers. The under sides are buff white with minimal brown streaking that is variable among individuals with the under wings white. Legs vary from green, green grey, yellow, green in front and yellow behind. The toes are long.

In breeding the plumage is brighter and upper breast feathers are longer and looser. In courtship the lower bill (of both sexes) flashes red briefly during copulation, nest relief, and other excitement. The lores and orbital skin flush dull red.

Variation: The female is smaller and a duller color. Its crest is black and less glossy than the male. It has a brown or rufous tinge to the dark colors, which also show some streaking. Wing patches are pale brown buff and slightly streaked. The under parts are striped in brown. There are no known differences between sexes in soft part color.

Geographic variation has been recognized in five subspecies. Payesii is smaller with shorter wings than minutus; the neck and wing patches are more red brown to chestnut rather than buff of minutus; the irises become red brown in courtship; legs in breeding are olive green in front and yellow behind.

Podiceps is smaller than minutus or payesii; the adult male has the deep rufous on the neck extending over the whole underparts and under wing and becoming chestnut on the upper parts; the immature bird is darker than minutus.

Dubious has a shorter, thicker bill; the neck and wing are chestnut to rufous; the flight feathers are dull black or dark grey brown contrasting with buff wing patch; the immature has pale primaries with fulvous tips; the female is not well marked.

Novaezelandiae was larger and darker, back and scapulars were dark red brown with rufous lining to the feathers; the hind neck was chestnut; the wing patch are spotted chestnut; the female was more heavily streaked below.

Juvenile: The juvenile bird is more boldly streaked below and above with a red brown tinge. The crown is streaked brown. The wing patches are heavily mottled with brown and buff.

Chick: The downy chick is pink buff above (minutus), reddish buff (payesii), pink buff to brown (dubious) and white below. Irises are black brown. The bill is dull pink turning to grey. The facial skin is blue grey becoming olive yellow. Legs and feet are olive grey with pink toes.

Voice:“Kohr” call is the distinctive and characteristic grunting or barking advertising call used during breeding. It is variously rendered as “kohr, kohr, kohr, kohr”, “hork, hork, hork”, “Cor, orr, orr, orr”, or “gogh, gogh, gogh, gogh” and also “hogh”, “rru” and “woof”. The “Kwer” call is a flight call. It is rendered as “kuk-kuk, kuk-kak”, cuck, cuck,cuck cuck”, Cra, a, a, a, k”, “quer” or “ker-ack”. It is low pitched and abrupt, and sometimes proceeded by a higher pitched “quee”. The “Koh” call is the disturbance call. The “Gek” call is a repeated call given frequently at the nest site, rendered as “gek, gek, gek, gek” or “ek, ek, ek, ek”. A similar “Gak” call is the alarm and threat call. It can be rendered as “kuk”, “gat”, “gack” or “yick”. The “Aark” call is an anxiety call. “Goo” call, rendered “goo, goo”, is used with the Greeting Ceremony. Young beg with “tu, tu, tu, tu, tu”.

Weights and measurements: Length: 25-35 cm. Weight: 140-150 g.

Field characters

The Little Bittern is identified by its small size, dark cap and back, and buff grey wing patches offsetting dark flight feathers. Its flight is rapid for a heron, flying with rapid, shallow, clipped wing beats, legs dangling, often dropping into cover. It is distinguished from the Yellow Bittern by being slightly larger, having a shorter bill, its black (not brown) back, and white to grey buff (not yellow buff) wing patch. It is distinguished from the Cinnamon Bittern by it dark (not cinnamon) back and cap.

Systematics

The Little Bittern is one of the small bitterns, Ixobrychus, that share similar plumage, white eggs, scutellate tarsi, and ten tail feathers. It is closely related to the Least and Yellow bitterns, with which it shares a slender bill, uniform dorsal coloration, and moderate plumage sexual dimorphism. The Little Bittern covers a large discontinuous range, with other small bitterns filling in the range gaps. Novaezelandia is often considered a different species, due to its larger size. Payesii and podiceps are also sometimes considered to be separate species.

Range and status

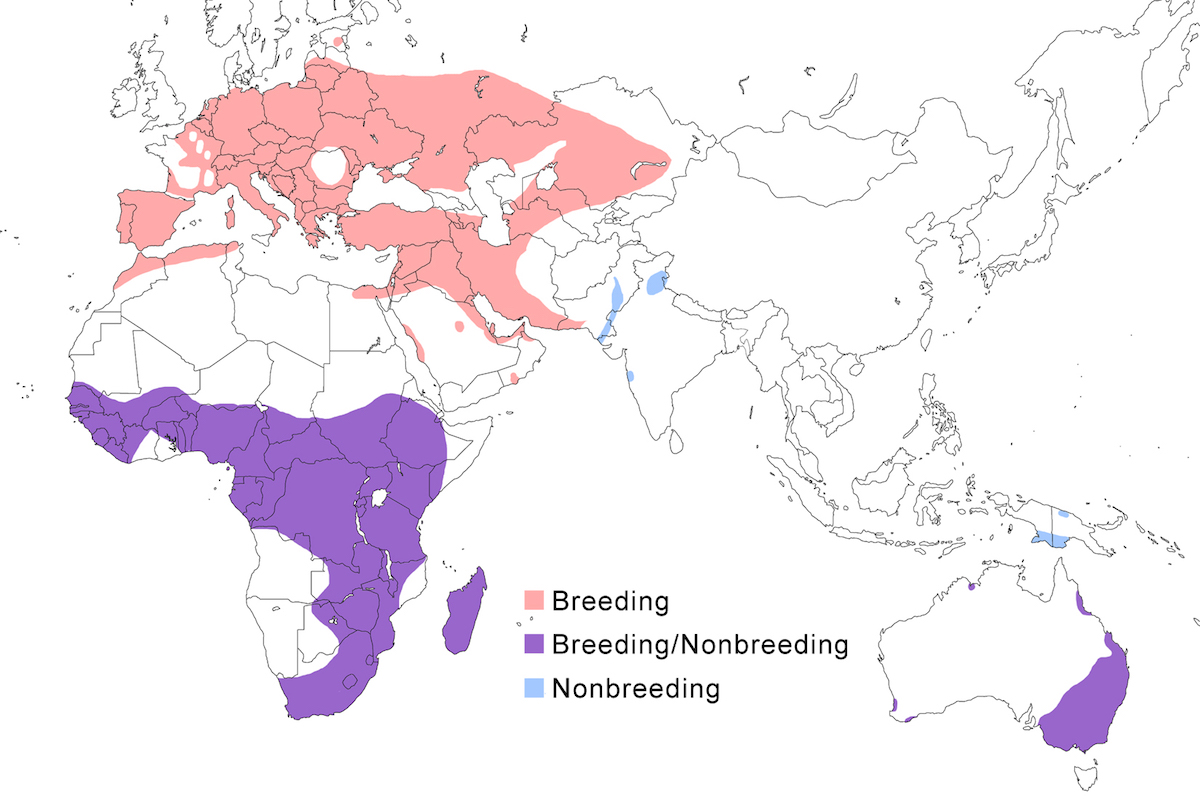

The Little Bittern occurs in Europe, west Asia, Africa, Madagascar, north India, Australia and New Guinea.

Breeding range: The north boundary of the breeding range of minutus includes England (Allport and Carroll 1989), Netherlands (Bekhuis 1990), Belgium, north Germany, to Estonia, Russia (west Siberia), Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan (Lopatin et al. 1992), Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgystan, west China (Sinkiang). It breeds in North Africa (Morocco to Tunisia, north Egypt – El Din 1992), Turkey, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain (possibly breeding), Iraq (possibly breeding), Iran, Pakistan (Sind), India (Kasmir – Holmes and Hatchwell 1991, Uttar Pradesh, Assam), and Nepal.

Payesii occurs in Africa south of the Sahara in Mauritania, Senegal (Morel and Morel 1989), Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Gabon, Principe, Nigeria, south Sudan, south Somalia, Uganda, Rwanda, Kenya, Tanzania (baker and Baker in prep.), south east Congo, Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Namibia, east and south South Africa (Transvaal, Natal, Cape Province). Podiceps is confined to Madagascar. Novaezelandiae occurred only on South Island New Zealand. Dubius breeds in Australia (Queensland, New South Wales, south Western Australia, north Western Australia – Jaensch 1988).

Nonbreeding range: Minutus from Europe and west Asia move south in winter. A few birds remain in west and south Europe (Mediterranean, Ireland, Britain, Germany, Netherlands, and north Africa) (Cramp and Simmons 1977, Nankinov and Kantarzhiev 1988). Most birds winter in Africa south of the Sahara, mostly in east Africa but also west to Senegal and south to as far as South Africa. Minutus from north India appear to remain there during nonbreeding. Podiceps is probably sedentary; there is some evidence of its moving to Africa in the dry season (Brown et al. 1982) but this is refuted (Baker and Baker in prep.). Dubius also appears to be mostly sedentary but it also occurs in New Guinea, mostly in the southern lowlands (Jaensch 1995, 1996). As far as is known these are wintering birds from Australia, although there remains a possibility of its breeding in New Guinea (Beehler et al. 1986).

Migration: Minutus is migratory across most of its breeding range and has a significant post breeding dispersal. Birds in Europe move south in August–October. They fly singly and in small groups at night. Western birds move through Italy, Spain and France and along the Atlantic coast (Nankinov 1999). They cross the Mediterranean and Sahara in a broad wave. Birds from the east cross Israel, Iraq, Arabia, and Egypt, also in a broad front. Movement in Africa is less clear. Return migration is in March–April. Birds regularly overshoot and land north of the breeding range.

Minutus in the Middle East are partially sedentary. Minutus from north India, payesii and podiceps, are at least partially sedentary, with local movements that are not clearly understood. Payesii shifts in response to rainfall and drought. Podiceps is now understood not to migrate occasionally to Zanzibar as suggested by Brown et al. (1982). Dubius is probably migratory, shifting after wetlands dry out (March–April) from south to north and inland to coast, and also to south Papua-New Guinea. Return migration to the southern breeding areas in Australia is in August–September.

The Little Bittern ranges widely in post breeding dispersal, moving in all directions. Dispersal records include Iceland, Faeroes, Azores, Madeira, and Canary islands and Scandinavia. Dispersal records in the east include Lord Howell Island and New Zealand (O’Donnell and Dilks 1988).

Status: The species is widespread and common in many areas within that range. It has been decreasing in Europe, especially from 1970’s to 1990's, due to habitat loss (Nankinov 1999). Its nesting distribution is now fragmented, and the species appears to be in a rapid decline in west Europe (Marion et al. 2000). Its overall population is 37,000-107,000 pairs, the range reflecting uncertainties in eastern Europe - Romania, Ukraine, and Russia - which together support the greater portion of the European population (Marion et al. 2000).

The Little Bittern is common in north Africa, is increasing in Egypt (El Din 1992) and is more common in Arabia than previously appreciated. It has been under-represented on surveys in Tanzania; a guess at its population there puts it under 10,000 adults (Baker and Baker in prep.). It is rare in South Africa, under 100 pairs. It is uncommon in Madagascar and known from only a few places. It is abundant in parts of India (1,000-2,000 pairs in Kashmir). The population in New Zealand went extinct for unknown reasons – it is one of a few contemporary herons that has suffered extinction (Hilton-Taylor 2000). The Little Bittern is rare and very localized in Australia. It has declined in and west Australia due to habitat loss but may be more common in other areas than is presently appreciated (Jaensch 1989).

Habitat

The habitat used by the species is varied across its huge range. Most typically it uses freshwater wetlands having thick herbaceous vegetation with trees or bushes interspersed nearby. These habitats include peat bogs, reed swamps, edges of lakes, pools, reservoirs, oases, swamps, wooded and marshy edges of streams and rivers, wet grasslands, mangroves, salt marshes, lagoons. In east Africa it prefers smaller, well-vegetated swamps, marshes and drainage ditches (Baker and Baker in prep.) It also can be found in forests. It occurs in lowlands and up to 1,500 m in Madagascar and 1,800 m in the Himalayas.

Typical herbaceous plants used in these habitats include Scirpus, Typha, Phragmites, Baumea, Juncus. Shrubs and trees used include Muehlenbeckia, Melaleuca. It uses human habitats including rice fields, ponds, crop fields, vegetable gardens, and sugar cane fields. Little Bitterns can be very tolerant of humans and nest in places regularly visited by people (Cempulik 1994).

Foraging

The Little Bittern feeds by Walking slowly at the water edge stalking prey from the ground or more characteristically from a perch. It also Walks Quickly using Crouched posture, with head forward, in rapid steps. It Stands at the edge of cover on a perch. It feeds with its head and neck withdrawn. As it sees a prey item, it slowly extends its neck and then stabs. It sometimes it feeds by pecking, jabbing the bill in the water, and using an insect for bait (Baumann 2000).

It is a solitary feeder generally within territories held long term. Its activity periods appear to vary. It is primarily crepuscular over much of its range, but feeds at night and also at times during the day. African birds are primarily diurnal (Langley 1983). When alarmed it assumes the Bittern Posture.

The diet is varied, fish (Perca, Esox, Alburnus, Blicca, Cyprinus, Gambusia, Gobio, Eupomotis, Leuciscus), frogs and tadpoles (Rana), reptiles, eggs and young birds (Olioso 1991), shrimp, crayfish, worms, insects such as crickets (Gryllotalpa), grasshoppers, caterpillars, water bugs, beetles (Notonecta, Naucoris), beetle larvae, dragonflies (Libellula, Aeshna), spiders. Diet differs in various places. In some places it has primarily a fish diet (Langley 1983, Holmes and Hatchwell 1991) and in other places such as Italy insects predominate.

Breeding

The nesting biology of the Little Bittern has been well studied (Langley 1983, Darakchiev et al. 1984, Gerard 1986, Hoyer 1991, Holmes and Hatchwell 1991, Boozic 1992, Lopatin et al. 1992, Cempulik 1994, Martinez Abrain 1994, Gaballero 1997). As expected over such a large range, its nesting season is variable. Nesting occurs in the spring in the north of the range, May–July in Europe and India. It is in the rainy seasons or just after the rainy season in the tropics. Nesting is May–July in north Africa; July–October in west Africa; June–September in Nigeria; May–September in Congo; July, November–December in Uganda; March–April; June in Zambia; April–May in Malawi; February, September, November–December in Zimbabwe; March in Namibia; June–February in South Africa, October–January in Australia.

The species nests in thick herbaceous vegetation, especially near open water pools. But it also in trees or bushes usually over water, and has also been found nesting in trees over dry land. The Little Bittern nests solitarily, but also and perhaps more typically in loose colonies with nests as close as 5 m but usually 30-100 m apart. It likely is extremely residential, in that nests may be reused in consecutive years (Barbier and Boileau 2000).

The nest is a platform with a conical base, 15-20 cm across, and 10 cm thick. In South Africa more substantial nests were 20-35 cm across. The nest is made of stems of herbaceous vegetation, lined with finer material. The nest is typically inserted in reeds, rushes, grass, or papyrus. However in some areas and situations, they nest in trees and bushes and make stick nests. It is built by the male, who starts during the display period.

Early in the breeding season, males establish breeding territories and give the Kohr call, staking out the territory and advertising. When calling, the lower bill flushes red. Territories are defended by an Upright display, Ground and Aerial Supplanting Attacks and a threat display in which the bird places its side to the opponent, spreading wings, lifting one and lowering the other. Males choose a nest site and begin building while continuing to advertise with the Kohr call. The males also use Circle Flights as part of the display. A flight also has been described in which the neck is extended and head held below the body.

Upon formation of the pair bond, birds participate in Contact and Non-contact Bill Clappering, during which the pair cross their necks. The Greeting Ceremony includes the arriving bird approaching the nest, with Bill Clappering, feathers raised, Crest Raising, and gives the Goo call. The bills flush red during the Greeting Ceremony. Upon completion, birds will Bill Clapper. Paired birds will remain together through the nesting season.

Eggs are chalky white. They are laid at intervals of 1 to 3 days. Size averages 36 x 26 mm in Europe, 34.6 x 26.6 mm in South Africa. Clutch size varies geographically, 5-6 in Europe and 3-4 in the tropics and South Africa (Langley 1983). The overall range is 2-7 eggs. Replacement clutches occur if eggs are destroyed but also after young fledge. In some case three broods are raised per year (such as in South Africa). Clutch size decreases later in season (Cempulik 1994).

Incubation, by both parents, begins with the first egg and lasts 16-20 days (Langley 1983, Homes and Hatchwell 1991). Hatching is asynchronous and chicks have their eyes open and legs are fairly developed after hatching. Young are fed in the first 2 days by food deposited on the nest floor. The parents guide the bills of the nestlings to the food. Thereafter, young grasp the parents’ bill and is fed directly. Chicks are brooded through 8-10 days.

Chicks grow relatively fast. By three days they beg by grasping the parent’s bill. Chicks assume the Bittern Posture when disturbed. Pinfeathers develop at 4 days. Sibling rivalry is low, despite asynchronous hatching. And there was not found to be a difference in growth rates relative to hatch order or brood size (Holmes and Hatchwell 1991). Chicks grow quickly and climb out of the nest in one week and can leave the nest entirely by 14-16 days. Maximum growth takes place at 15 days (Langley 1983). The birds fledge flying strongly in 27 days. Success was 56.6% of eggs hatching to nest departure in South Africa and 70-71 in India (Langley 1983, Holmes and Hatchwell 1991).

Population dynamics

Females can nest before their second birthday (Langley 1983). Nothing is known about the demography of this species.

Conservation

The conservation of this species is made difficult by its large range and multiple forms. Given the disjunct distribution of the presently recognized subspecies each with its own situation, conservation should be focused on each population. The European population has been decreasing for some time in some areas but is increasing or even expanding in other areas. It is more widespread in Arabia and the Middle East than previously appreciated (Perennou et al. 2000). The situation in west Europe is clearly critical, however. The population there is continuing to decrease. In Belgium, Netherlands, and France decreases are associated with habitat alteration. However, the general European decrease continues despite this being a species that is tolerant of human alterations and despite the continued availability of apparently suitable habitat. The European population is migratory, and it may be that juvenile or adult mortality in migration and wintering may be a one cause for the widespread decrease. Its populations in east Europe are probably high, but the data are insufficient to detect trends. The Indian population appears to be stable. It is crucial to locate the important nesting areas for this population and undertake protective measures.

The African breeding population is widespread but uncommon in all regions (Turner 2000). Although the two subspecies can be told apart, the existence of widespread wintering by European and west Asian birds makes interpretation of the African breeding population difficult.

The Australian population is considered to be uncommon, but rather appears to be concentrated seasonally in a few highly suitable breeding sites. It has declined and had to shift its distribution due to past hydrological changes in its rivers (Maddock 2000). It is classified as Endangered in Victoria (NRE 2000), where it represents only 0.7% of bird observations in the state since 1970 (Scientific Advisory Committee 1997). Management and conservation of these river systems are critical to the species in Australia. It has been found breeding outside its known range, and evidence of further range expansions should be sought.

The Madagascar population may be down to 100 pairs and is known from a few widely scattered sights. This is a population that is at risk due to habitat alteration and should be considered Vulnerable. The New Zealand population is extinct, having last been seen over 100 years ago. The extinction of this recognized and distinctive subspecies (Hilton-Taylor 2000) suggests the potential precariousness of populations elsewhere. With dispersal arrivals from Australia it is possible that the species will re-establish itself there. The birds in New Guinea are probably migrants from Australia.

Research needs

The causes of the population decrease in west Europe need to be investigated through demographic study of the roles of migration and nonbreeding adult and juvenile mortality. This may require additional banding studies on the breeding ground and also related study in the wintering area. Comparative simultaneous study of east European populations would allow comparisons to be made. Drought, habitat change, loss of staging wetlands in the Sahara and Sahel, and conditions of wintering wetlands could be key environmental factors to be investigated. Surveys should be undertaken of the Madagascar population of the Little Bittern to determine important areas for remaining birds. Surveys should also be undertaken to determine the breeding status in New Guinea. The taxonomy of the species and subspecies of the small bitterns, particularly of the Little/Least/Yellow Bittern group, should be re-examined. At the same time, patterns of geographic variation and the subspecific taxonomy of the several disjunct populations of the Little Bittern should be undertaken, including using molecular techniques.

Overview

The Little Bittern is a bird of dense marsh vegetation, in which it feeds and nests. It forages in the typical bittern manner of Walking and Standing on marsh plants, old nests, or branches. It catches a diversity of prey, but primarily fish or insects, depending on the locality. It is a solitary feeder returning to its territory daily. By maintaining its territory, it has knowledge of its feeding site and avoids competition or disturbance of its prey. It remains paired through the nesting season and typically renests one or more times if the breeding season is long enough. Although young hatch asynchronously, in the situations so far studied, there is no difference in growth or survival of late-hatched young.