White-faced Heron

Egretta novaehollandiae (Latham)

Ardea novaehollandiae Latham, 1790. Ind. Orn. 2, p. 701: New South Wales.

Other names: Blue Crane, White-fronted Heron in English; Garceta Cariblanca in Spanish; Héron à face blanche in French; Weißwangenreiher in German; Canguk australia in Indonesian.

Description

The White-faced Heron is a medium size light grey heron with a distinctive white face.

Adult: The adult is basically light blue grey with a distinctive white head including the forehead, crown, side of head, chin, and upper throat. Crown pattern is variable with the white sometimes extending down the neck, the variability being sufficient to make recognition of individual birds possible (Maddock 1991). Iris color also is variable, grey to green to dull yellow to cinnamon. The lores are grey black. The bill is black with the lower bill tending to pale grey at the base. It has pink brown tones on shoulders and flanks. The chest has distinctive, long pale chestnut to bronze lanceolate plumes. Under parts are very light pale grey. In flight the wing appears barred, with lighter wing feathers contrasting with darker flight feathers and leading edge. The flight feathers have black tips. Grey lanceolate plumes occur on the back. The tail is dark grey. The legs are green yellow to orange brown.

During breeding season, plumes become brighter, more numerous, and more prominent, grey on the back and chestnut on the chest. Lores turn grey black and legs pink orange (Maddock 1991).

Variation: Female is smaller. Other variation in size and darkness has been described, which may be geographic. This observation has led to the description of several subspecies, novaehollandiae and parryi from Australia, nana from New Caledonia, and austera from Irian Jaya. Albinistic individuals occur (Heather 1983, Selby 1997). The extent and dispersion of variation in the species requires additional examination.

Juvenile: The immature White-faced Heron is paler and duller than the adult, with brown grey shading on forehead and sides of head, making these features less white than in the adult. There is a narrow pink buff throat line. The underparts are brown grey. The chest is buff pink, without the chestnut of the adult. Immature birds lack lanceolate plumes on either their chest or back.

Chick: Chick is covered with grey down.

Voice: The “Graak” call, also rendered “graaw”, is the species’ most common call, given in flight, in interactions and aggressive encounters such as Supplanting Flights. The “Gow” call, rendered “gow, gow, gow”, is given on return to the nest. The “Graak” call is also given upon approaching the nest. A high-pitched “Wrank” call is an alarm call. An “Oo” call, rendered “ooooooh”, and “Arg” call, rendered “aaarrrgh”, are given as alarm calls including when taking flight. A “Crock” call, rendered “crock, crock, crock, crock”, is used in Stretch display. A high-pitched “Garik” call is a contact call.

Weights and measurements: Length: 58-66 cm. Weight: 500-550 g.

Field characters

The White-faced Heron is identified by grey body color and white face. It is a slender and graceful bird with a distinctive flight, slow and deep with bowed wings creating a graceful down beat. The neck is more frequently seen extended when in flight than in most herons, possibly because it tends to move only short distances when disturbed.

It is distinguished from the Grey Heron by its smaller size, white face, slenderness and graceful appearance. It is distinguished from the dark phase of the Eastern Reef-Heron by its more slender bill, white face and darker body, and barred under wing. It is distinguished from the White Necked Heron by its white face (not entire head and neck), white upper throat (without black throat spots), and light green to brown (not black) legs. It is distinguished from juvenile Pied Herons by having a white face (but not head), dark (not light to white) breast, and bicolor wings (without a white patch).

Systematics

This species has always been considered to be closely related to Ardea, but for some time it was placed in its own genus due to absence of the plumes typical of Ardea. Its basic appearance and behavior are more Egretta-like. Moreover, biochemical DNA analysis revealed it as a typical Egretta (Sheldon 1987).

Infraspecific variation is unclear. Although several subspecies have been described in the past, more recently, the species has been considered monotypic (Marchant and Higgins 1990). This is an individually variable, eruptive and fast spreading species, suggesting range wide study is needed of geographic variation.

Range and status

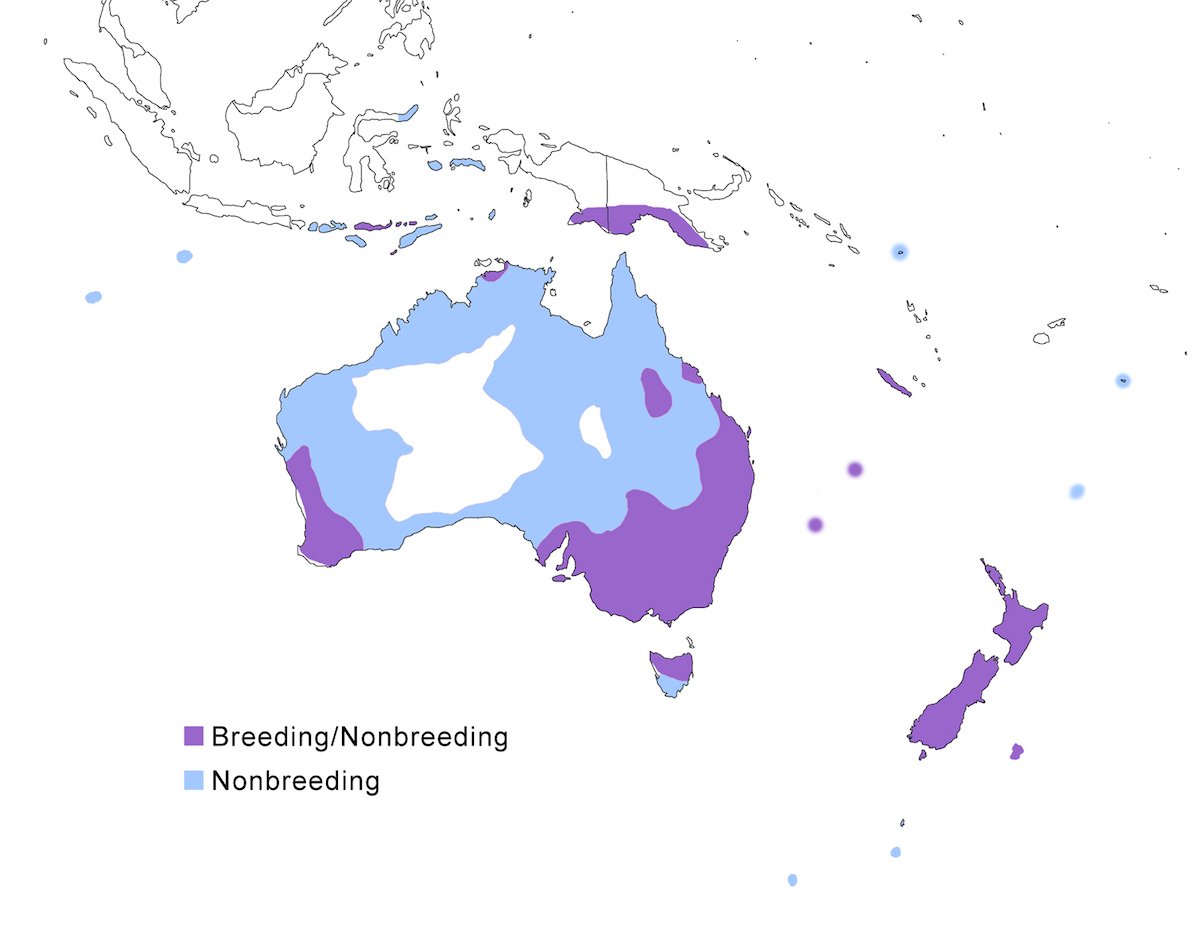

The White-faced Heron is a bird of Australia and nearby East Indies.

Breeding range: The White-faced Heron breeding range includes Lesser Sundas and Moluccas Islands, south New Guinea, Australia except the inland deserts, the near-shore islands, Tasmania, Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands, New Zealand, Chatham Island (Hemmings and Chappell 1988). Although now resident on Christmas Island, it is not recorded yet as breeding.

Migration: The species is best described as locally nomadic. Birds regularly wander widely, sometimes apparently for long distances, given its ability to colonise distant islands. It also has regular seasonal movements. In New Zealand, herons move inland annually in winter. In Australia, they move inland during nesting season to flooded wetlands and then move back to the coast post breeding. Herons accumulate in wet areas during annual dry seasons and droughts.

Dispersal records occur throughout much of Australasia into the Indian Ocean. It is commonly found on Lombok, Flores, Sumbawa. Other dispersal records include Cocos-Keeling (Stokes et al. 1984), Tonga (Gill 1988, 1990), Sulawesi, Kermadec, Aukland, Soloman, Campbell, Snares and Macquarie Islands, and recently as far north as Xiamen Island (China) (Chen et al. 2000a, b).

Status: It is the most common and widespread heron in Australia and Tasmania. It has been increasing its range in Australia and is now the most abundant heron in New Zealand. The change in status in New Zealand is impressive (Carroll 1970). It was first reported there in 1868; first reported as a breeding species in 1941, and has increased expansively since the 1960's. Although first established along the coast, it is now found throughout both main islands.

Habitat

The White-faced Heron is highly flexible and uses a wide variety of habitats featuring shallow water. Its occurrence in an area often depends on water conditions (Robertson and Heather 1999). Habitats used include tidal mud flats, sea grass beds, mangroves, reefs, saltpans, saline lakes and lagoons, beaches, dunes, rocky shore, lakes, stream margins, natural ponds, billabongs, farm ponds, ditches, seasonally flooded grassland and pasture, and reservoirs. It also uses drier sites such as pasture, golf courses, urban parks, gardens, orchards, roadsides, and garbage dumps. It occurs as high as 1,700 m in west New Guinea.

Foraging

White-faced Herons are active diurnal feeders, although they have been reported as feeding at night as well (Higgins and Smith 1999). Typically, they forage mostly by Walking slowly, Walking Quickly or Standing, all in Upright or Crouched posture. They use Walking slowly to stalk their prey in shallow water or on dry ground. They Walk Quickly on land, exposed mud or at the water’s edge. They break into Running, chasing after prey, often extending and flapping wings to hop across the water. Their direction of movement is influenced by foraging conditions, such as glare (Davis 1986b). They frequently use Foot Stirring and Foot Raking in shallow water. Other behaviors seen are Head Tilting, Gleaning, and Wing Flicking.

White-faced Herons generally feed solitarily defending well-spaced territories, especially during the nesting season (Lowe 1983, Moore 1984). The also feed rather independently within loose small groups. They use Alert Posture upon disturbance. Aggressive interactions are the Forward display, Upright display and Supplanting Flights. In the Forward, birds raise the plumes on their chest and back and walk towards the intruder or walk in parallel, a behavior that can develop into birds doing parallel strutting runs. In the Upright, the plumes are not raised. Supplanting can begin with one bird running after another or attacking from flight, often with a Graak call. Bill Jabbing has been reported, flying into the air while doing so. The Crouch is used as a submissive posture. Although large birds, they are at times subject to harassment by other species and potential predators (Rowe and Rowe 1998).

Although usually solitary, in the nonbreeding season and in terrestrial habitats they have been seen to feed in groups of dozens of birds, particularly after heavy rain or flooding (Maddock 1991). They have frequently been observed in flocks of more than 50 foraging for insects deep within a tall lucerne crop, virtually hidden by the foliage, and in a similar sized flock, in company with Cattle Egrets, following a cultivator retrieving grubs it exposed (M. Maddock pers. comm.). When feeding outside the nesting season especially in flocks, aggressive interactions are rare and they appear not to defend their individual space. They also feed commensally following other foraging birds such as ibises, cormorants, and spoonbills (Davis 1984, 1985, Maddock 1991, 1992). They even defend their ‘beaters’.

Adult herons are more efficient than juveniles (Davis 1984, Lo and Fordham 1986). Herons tend to feed on whatever is most available, and feeding intensity and success vary seasonally (Lo 1991, Lo and Fordham 1986). They frequently roost at times during the day on trees, rocky cliffs or wetlands, particularly between tides. They also may alternate between terrestrial with aquatic feeding sites during the day. They are known to roost at night with other colonial waterbirds such as egrets, ibis and cormorants (M. Maddock pers. comm.).

White-faced Herons feed on a wide variety of prey especially fish, crustaceans, and terrestrial invertebrates. Prey items appear to mostly be small (Davis 1984). Recorded food includes many species of fish, shrimp, crabs, frogs, worms, snails, amphipods, and insects (mayflies, stoneflies, bugs, lacewings, orthopterans, beetle larvae, lepidopteran larvae, flies). In New Zealand they eat the introduced Australian tree frog (Hyla). They consume flies at garbage dumps (Hobbs 1986), but previously accepted reports of this heron eating carrion are now doubted (Garnett 1993). They may eat vegetable material, but this too needs further study. Diet varies between the coast (aquatic invertebrates) and inland (fish and terrestrial invertebrates), and also seasonally (insects in summer to earthworms in fall) (Lo 1991).

Breeding

This heron breeds during rainy periods when its feeding habitat floods, which occurs variably from year to year and from place to place in Australia. It is similarly variable in its nesting cycles, and in Australia it has been recorded nesting in nearly all months. The most common starting dates are August to December, with a more constrained season in the southeast. In New Zealand, it nests starting in June peaking in October.

It has been recorded as nesting in many species of trees, from 4 to 40 m high, typically in open country near fresh or salt water and avoiding forests. Nesting trees are solitary or in small groves in open landscapes. It appears to prefer pastures with scattered trees and nearby pools. It flexibly nests in mangrove swamps, rice fields, along roads, in golf courses, edge of wood lots, orchards, salt plains, suburbs and urban parks. On islands, it nests along shore or shore cliffs on rocks or small crevasses. Sites are reused in successive years. It nests from sea level to over 1,000 m.

Nesting dispersion is variable. Over most of its range, these herons are solitary nesters. They nest within defended areas, measured at 2-3 km apart. They also nest in scattered groups and they have been reported nesting in colonies in the largest wetlands.

The nest is a platform of twigs lined with grass. They are often flimsy structures, about 40 cm wide and 10 cm thick. But they can also be substantial, particularly when re-used in successive years. They are placed in crotches of trees or out on limbs, sometimes far out from the trunk. Nests are sometimes placed over water, but this is far from required as some nests are many km from water. The adaptability of the species is shown by its willingness to nest on artificial structures (Wall 1986). Both sexes attend the nest site and nest. Building the nest takes 12 days. One bird gathers twigs; the other inserts them with the Tremble Shove motion.

The courtship of this species is hardly ever observed and may be subtle due to familiarity of neighboring birds. Courtship that has been observed takes place at the nest site, in the nest tree and nearby trees, and likely (although not proven) on the feeding grounds. Twig Shake, Back Bite, Wing Preen, Bill Clapping, Circle Flight and mild Forward displays have been reported (Lo 1984, Maddock 1991). The Stretch includes low Crock call. In the Circle Flight the neck is outstretched and the Grar call is given.

The eggs are blue to green-white. They average about 48.51 x 34.3-35 mm. Clutch size ranges from 2 to 7 eggs, more usually 3 or 5. Incubation begins after the second egg. Replacement clutches occur, and a pair has been reported to have raised a brood even after five successive clutches of 5 eggs each had been collected from the nest. Incubation is by both sexes, lasting about 24-26 days. Both sexes attend the nest site and nest. The Greeting Ceremony on nest change-over involves raising the plumes, Bill Clappering, Preening, and giving the Grak call.

Young hatch asynchronously. In the early stages of chick rearing, one parent remains with the young but after 9 days the chicks are left unattended while the adults forage for food (Maddock 1991). Both parents feed young and constantly guarded them to 3-4 weeks. Food is brought at intervals of 40-70 minutes with frequency decreasing with age. The chicks seize the parent’s beak crossways to stimulate regurgitation. Competition occurs among chicks. The young, if alarmed, adopt a Bittern Posture. The breeding season is very extended, lasting up to eight months. Fledging takes 40 days after hatching. Adults feed fledged young away from the nest site (Moore 1984). The juveniles may stay with their parents as late as the next nesting season, probably learning how to feed (Davis 1984).

There are few studies on breeding success. One study over 5 breeding seasons recorded a mean success of 1.4 young per nesting attempt, or 1.75 per successful nest (Maddock 1991). Nests and nestling are lost to storms and predators including Kookaburra (Dacelo), magpies (Gymnorhina), harriers (Circus), and owls (Ninox) (Evans 1986, Geering 1988).

Population dynamics

Nothing is known about the population dynamics of this species.

Conservation

This is an abundant and widespread species that has been expanding its range in the past century (Maddock 2000). As a generalist in habitat choice and prey selection, it has been able to take advantage of many of the changes in the Australian and New Zealand landscape brought about by human development. Forest clearing, irrigation of pastures, farm ponds and reservoirs, and introduced prey have been advantageous to this species. Being solitary, it uses and protects its food supply during the nesting season. Being a solitary nester in remnant trees and a species that avoids forests, it is not disadvantaged by land clearing. This is a species for which conservation concerns are local. It is so ubiquitous that it may be an environmental indicator, specifically useful in the continent-wide monitoring of contaminant loads (Davis 1984).

Research needs

The extreme adaptability of this species makes it a candidate for study of its ability to respond to environmental fluctuations. Much is known about its basic foraging and food habits. Nesting success in relation to food supplies, survival in relation to environmental conditions, overall demography, residency and movement patterns of individuals, mate choice and courtship behaviour, and the extended period of juvenile dependence need to be better understood. The parallels between the White-faced Heron and the Cattle Egret, both of which have expanded their ranges and feed in man-altered terrestrial environments, deserve additional comparative study. Its potential role as an environmental indicator might be examined. Understanding interactions and relationships among nearby territorial herons may reveal much about the biology of solitary herons. Studies of marked birds should be used to determine year-round interactions among neighbouring birds and also their long-dependent young. Study is needed of geographic variation to determine if there are bona fide subspecies to be identified. The relation of this species to Egretta on the one hand and Ardea on the other should be further studied, especially using molecular techniques.

Overview

The White-faced Heron is an opportunistic heron adapted to taking advantage of changeable hydrologic conditions by feeding, nesting, and moving according to wet-dry cycles. It is one of the more generalist of all the herons. It is a solitary species, but one that can also feed or nest in loose aggregations or even large flocks when the situation allows. It is mainly sedentary, but locally nomadic according to conditions. It is a flexible feeder, taking a wide variety of prey from a wide variety of terrestrial and aquatic habitats and changing diets. It appears to depend for nesting on aquatic habitats, where it eats fish and aquatic invertebrates. However, it just as typically forages on damp grasslands. It defends all-purpose breeding and feeding territories during nesting but is less aggressive outside the nesting season. Much can be learned from this species about flexibility among solitary herons.