Black Bittern

Black Bittern

Ixobrychus flavicollis (Latham)

Ardea flavicollis Latham, 1790. Index orn., 2, p. 701: India.

Subspecies: Ixobrychus flavicollis australis (Lesson), 1831: Timor; Ixobrychus flavicollis woodfordi (Ogilvie-Grant), 1888: Solomon Isles, Aloa.

Other names: Yellow-necked Bittern, Mangrove Bittern in English; Avetorillo Negro in Spanish; Blongios à cou jaune in French; Schwarzdommel in German; Takasago-kuro-sagi in Japanese; Mangansile in Pilipino (Philippines); Kokokan sungai in Indonesian; Hei Yan in Chinese.

Description

The Black Bittern is a medium black or dark brown heron with a brown and white striped throat bordered by yellow.

Adult: In the male, the head and hind neck are dark grey black with a blue sheen. The relatively long bill is dark but variable. The upper bill is dark brown to red brown. The lower bill is pale green or purple below, but sometimes suffused with a reddish tinge with a yellowish tip. The irises are yellow to red brown and the skin around the eye is variable, dusky to green or pink. The chin, throat, neck and upper breast are deep buff streaked with black and white and bordered on each side by a paler gold yellow band from the chin to the base of the neck. A loose tuft of elongated feathers on the foreneck overhangs the upper breast. The back, tail and upper wing are grey black, with the wing coverts tipped in buff. The under parts are dark grey brown, often with a yellow wash. The legs are variable black, dark brown, or olive green with yellow green soles.

Variation: The female is slightly paler, generally brown grey instead of dark grey black, with more yellow wash to under parts. The female also has throat, foreneck, upper breast streaked with yellow, white and black with yellow breast plumes.

Birds vary individually and geographically. Individual variation is great. In Australasia, six plumage morphs have been recognized (Mayr 1945). All black and mostly white individuals have also been found (Payne and Risley 1978).

Described geographic variation is ascribed to three subspecies. Flavicollis, as described above, has the least amount of plumage variation. Compared to flavicollis, australis tends to be larger and variable. Males from Bismarck archipelago are mostly black with brown streaking on the throat and some females have brown grey under parts. Other morphs have been reported within this subspecies’ range. Compared to australis, woodfordi is slightly smaller, has a relatively longer bill, and males are darker below with narrow white streaks on breast and foreneck. Patterns of geographic variation are not clear given the vast amount of individual variation in the species.

Juvenile: The immature bird has a grey black crown, but appears duller with a rufous wash. The breast is brown streaked in yellow. Back feathers are edged in buff. Lores are green brown. Irises are yellow. Legs and feet are brown grey.

Chick: The downy chick is white with light brown tinge to neck and rump. The irises are black brown becoming dark brown. Bill, lores, legs and feet are light pink.

Voice: The “Whoo” is a low booming drum like call, a peculiarity of this species among the Ixobrychus bitterns. It is long, drawn out, rendered “ wh, o, o, o, o, o, o”, given at 15 s intervals and answered by neighboring birds. It undoubtedly is a territorial and advertising call. A soft “coo-oorh” call is given approaching the nest. Other calls have been reported but need to be clarified.

Weights and measurements: Length: Very variable, 55-65 cm. Weight: 275-358 g.

Field characters

The Black Bittern is identified by its size, dark back, striped neck bordered by a striking yellow streak, and its long bill. It is usually seen flying away into thick cover. It is distinguished from the other Ixobrychus bitterns by its dark back color with yellow neck and its larger size. It is distinguished from the Gorsachius night herons and the New Guinea Tiger-Heron by its uniformly dark plumage and disproportionately long dagger-like bill. It is distinguished from the Green Backed Heron by its uniformly dark upper parts, yellow patch and breast stripes.

Systematics

The Black Bittern is one of the Ixobrychus bitterns, but is the largest of the group. It is similar morphologically but uniquely has a booming call (Payne and Risley 1976). It also has a distinctive skull shape, related to its very long bill. It was previously assigned its own genus. Its skull and color pattern are most similar to the Dwarf Bittern.

Range and status

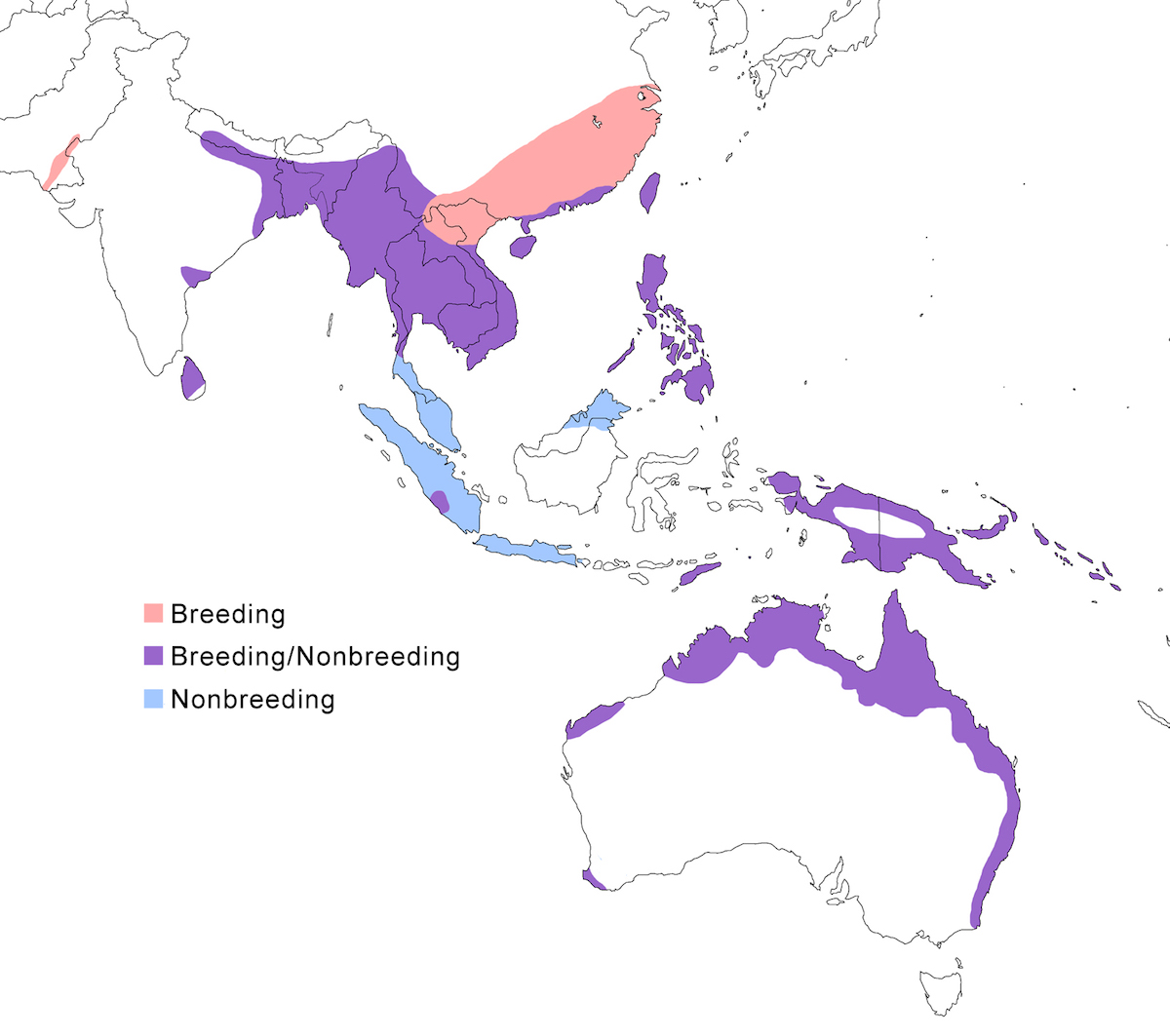

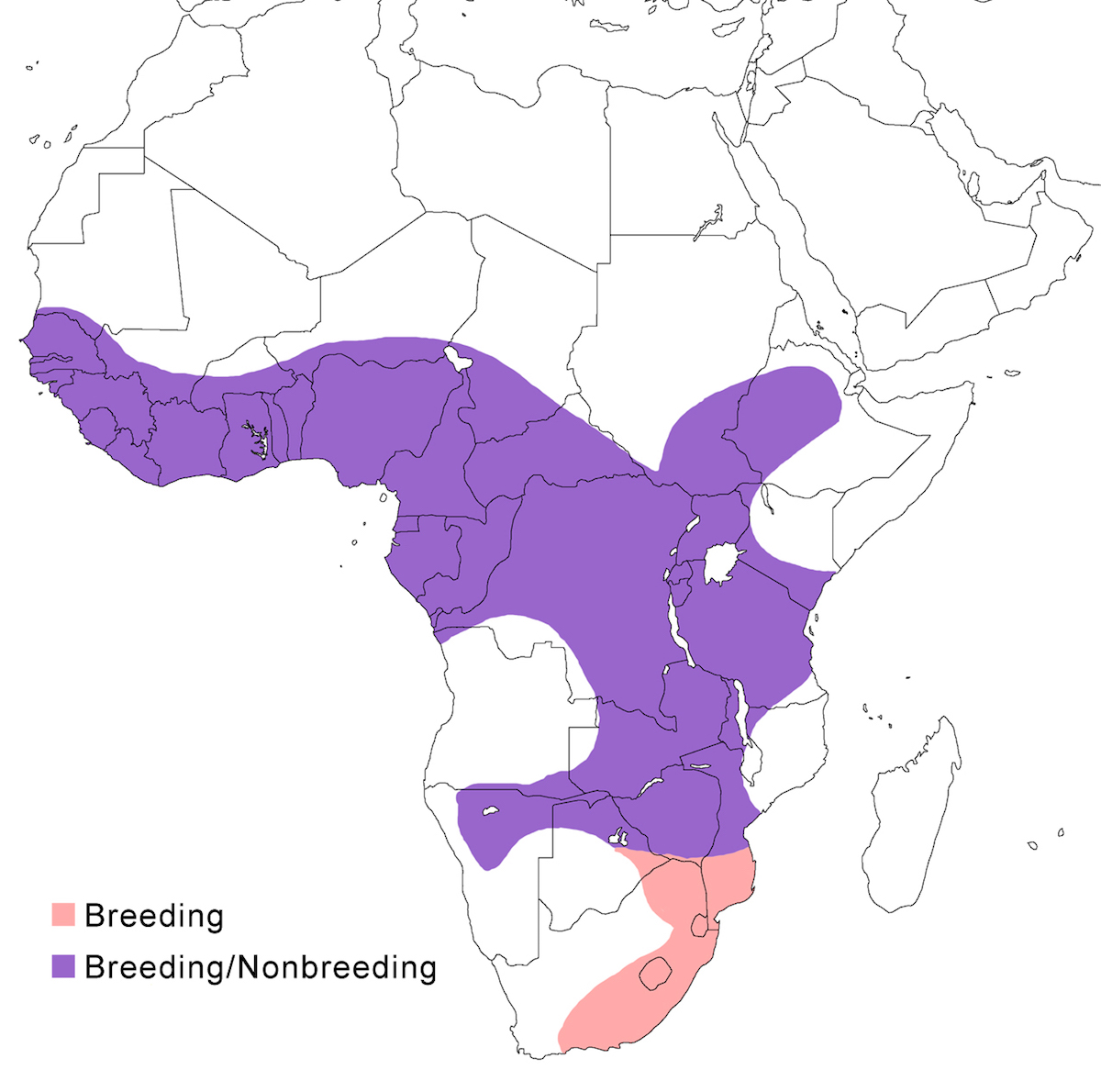

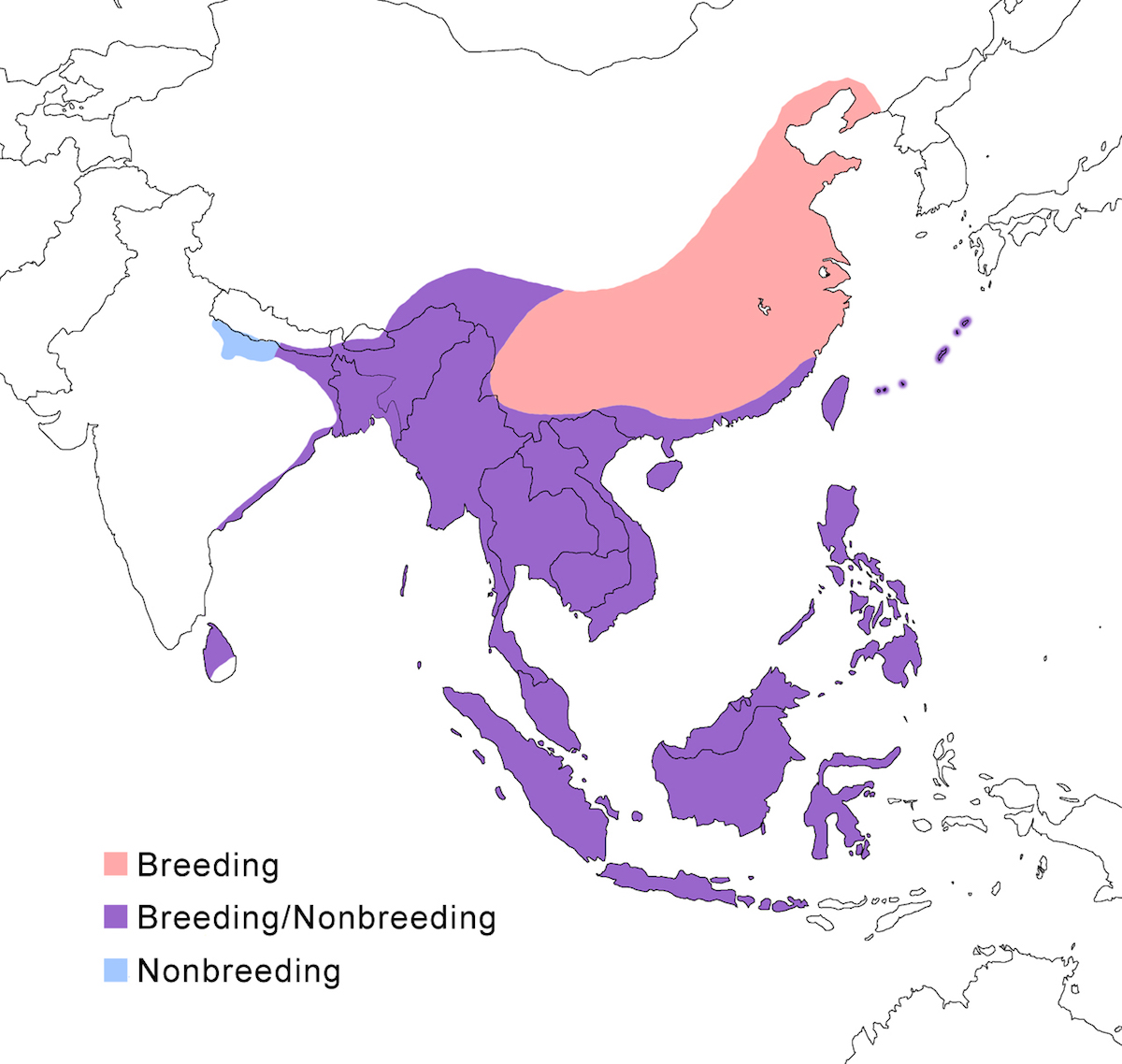

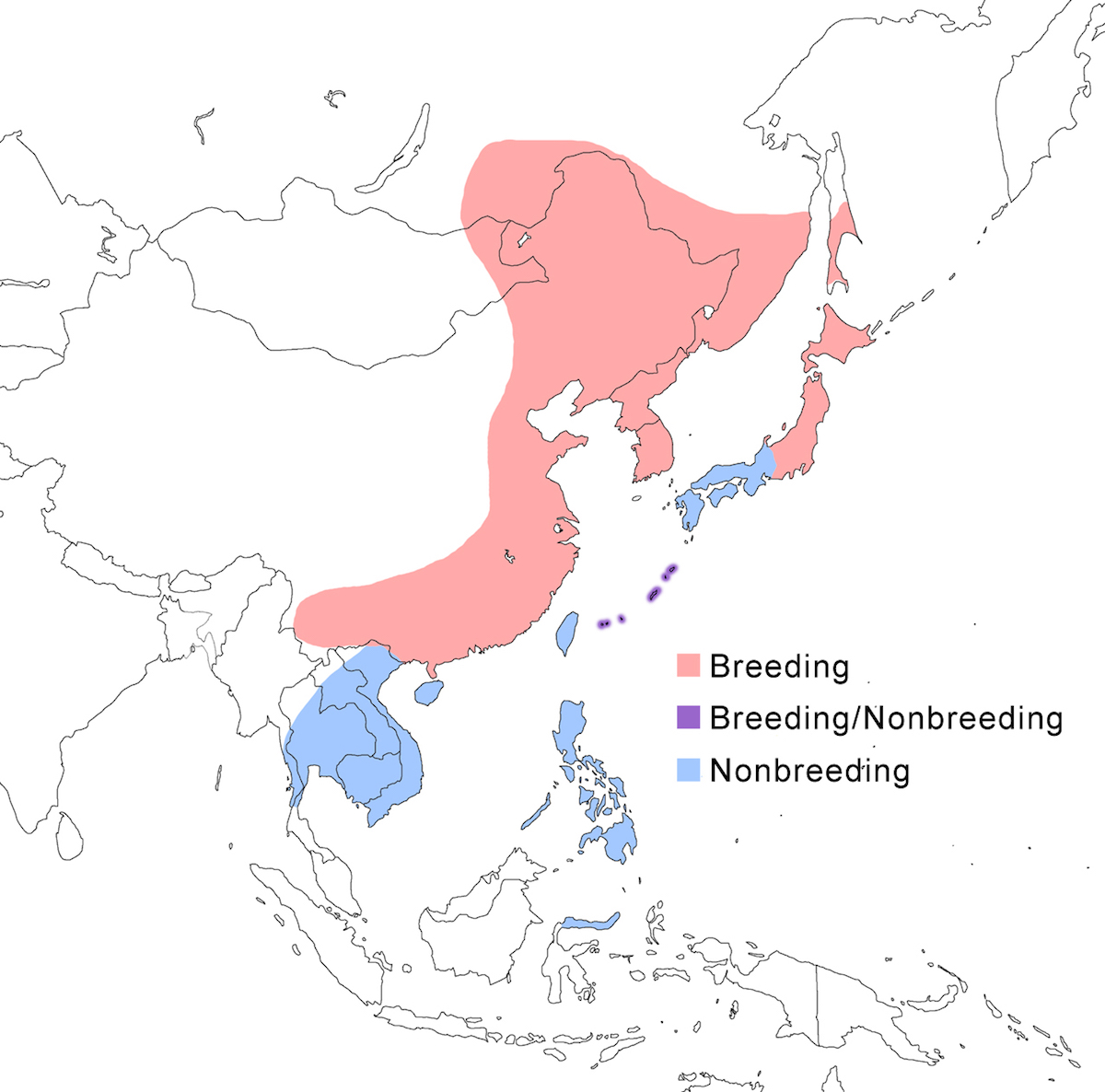

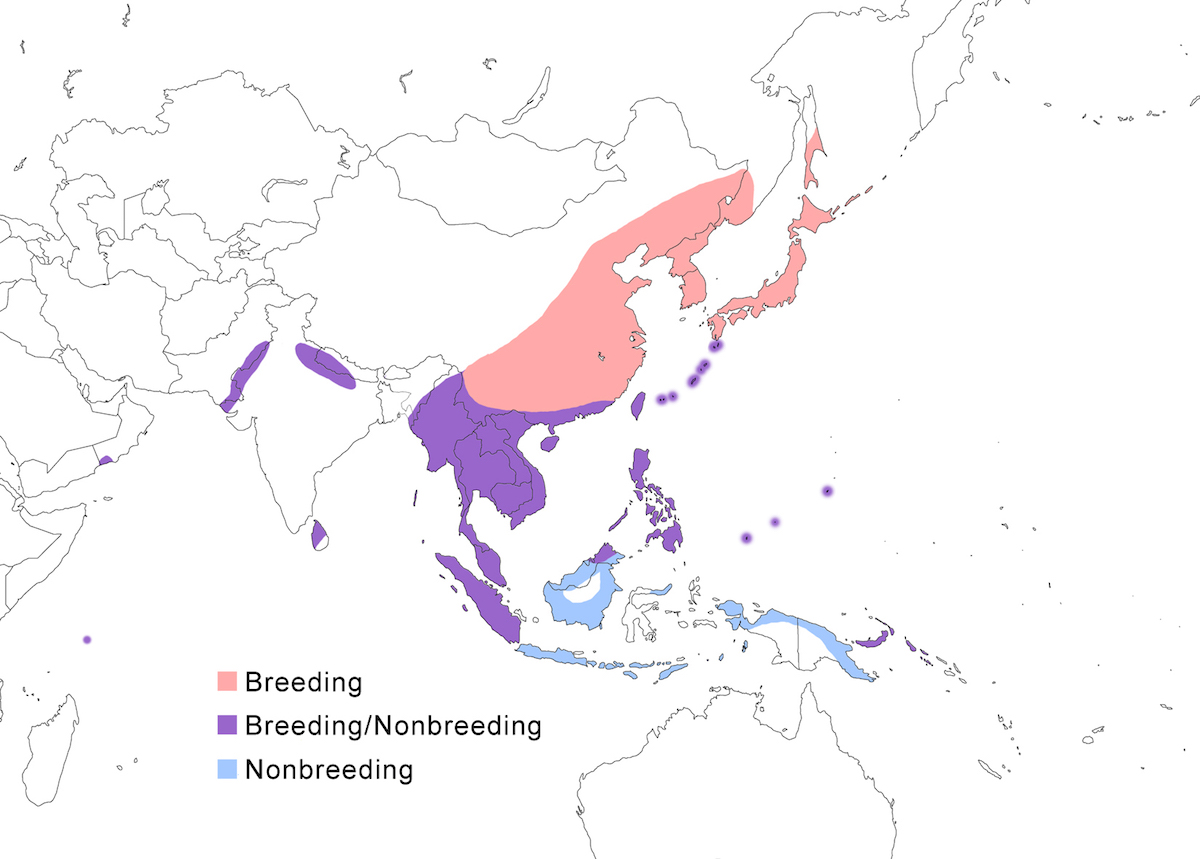

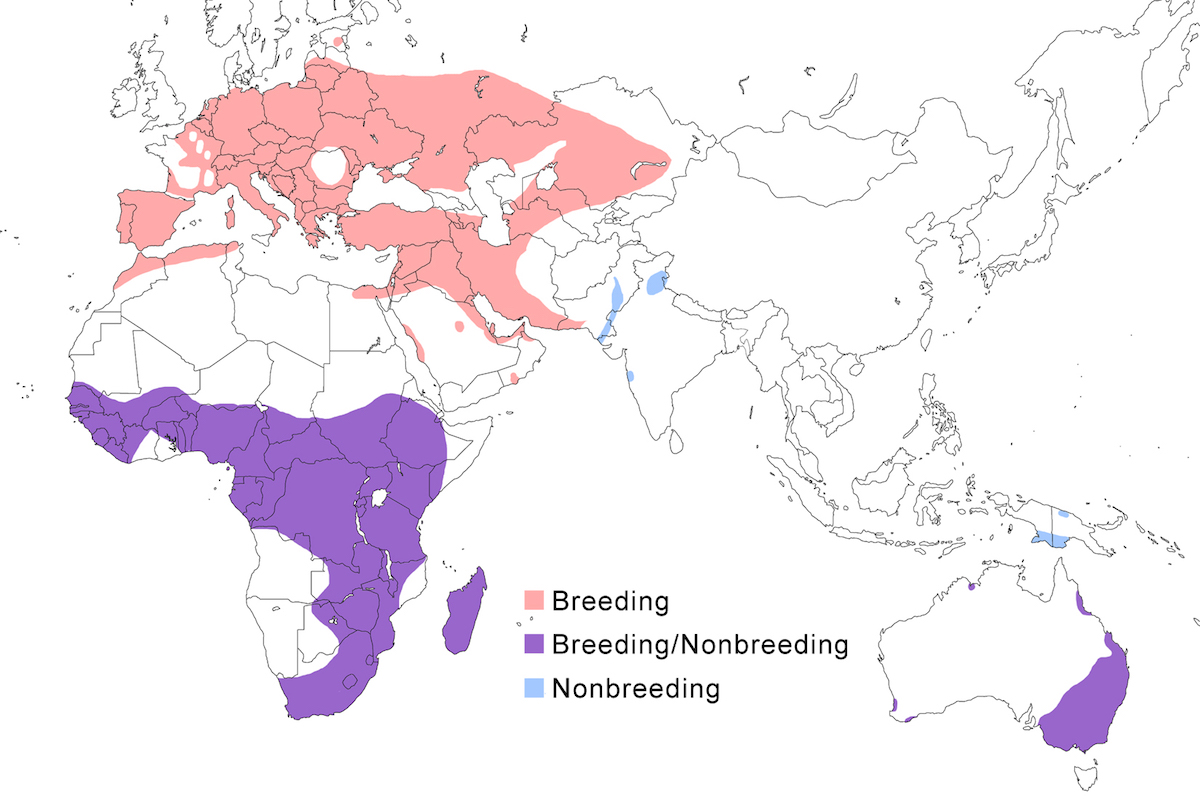

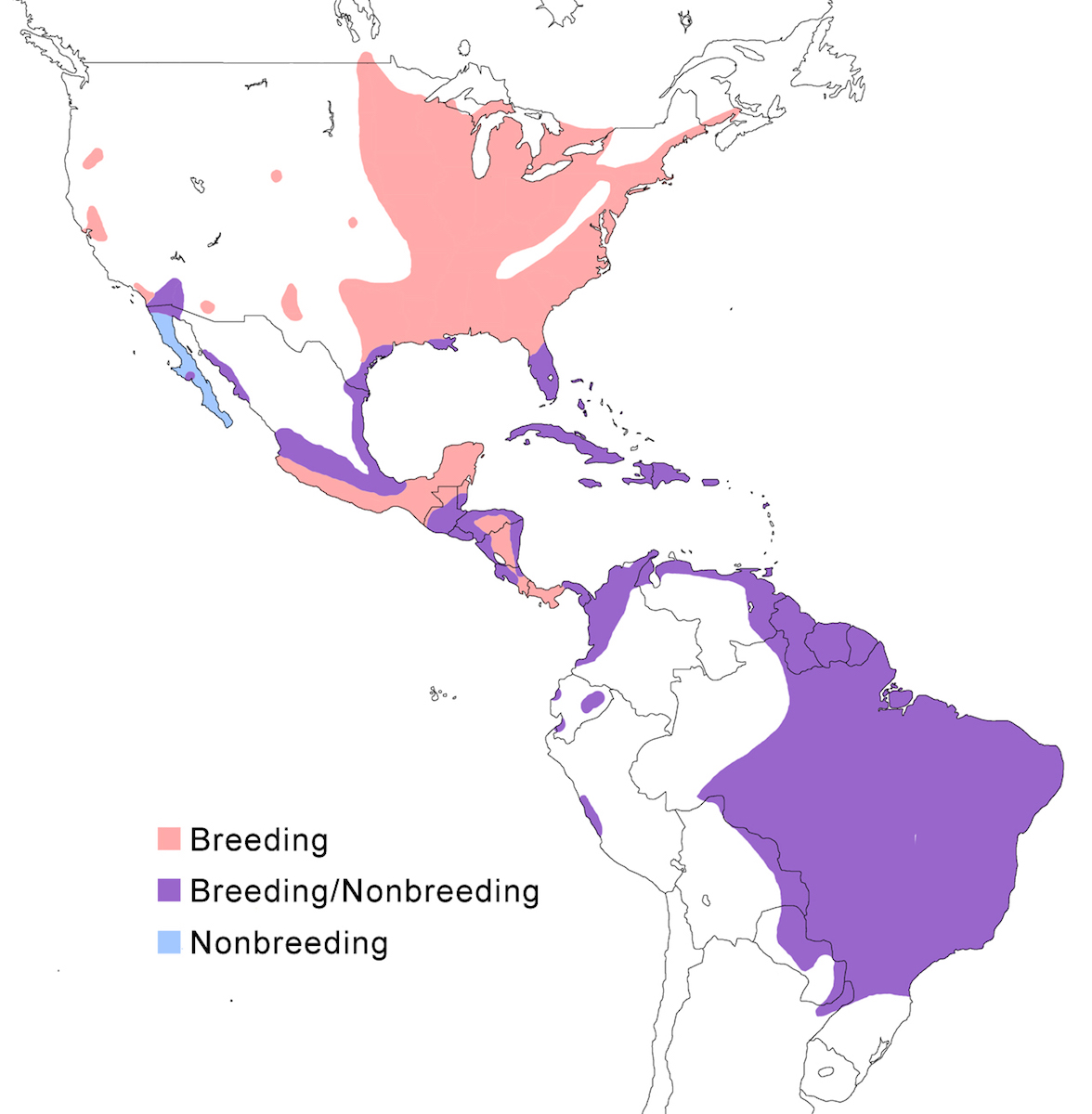

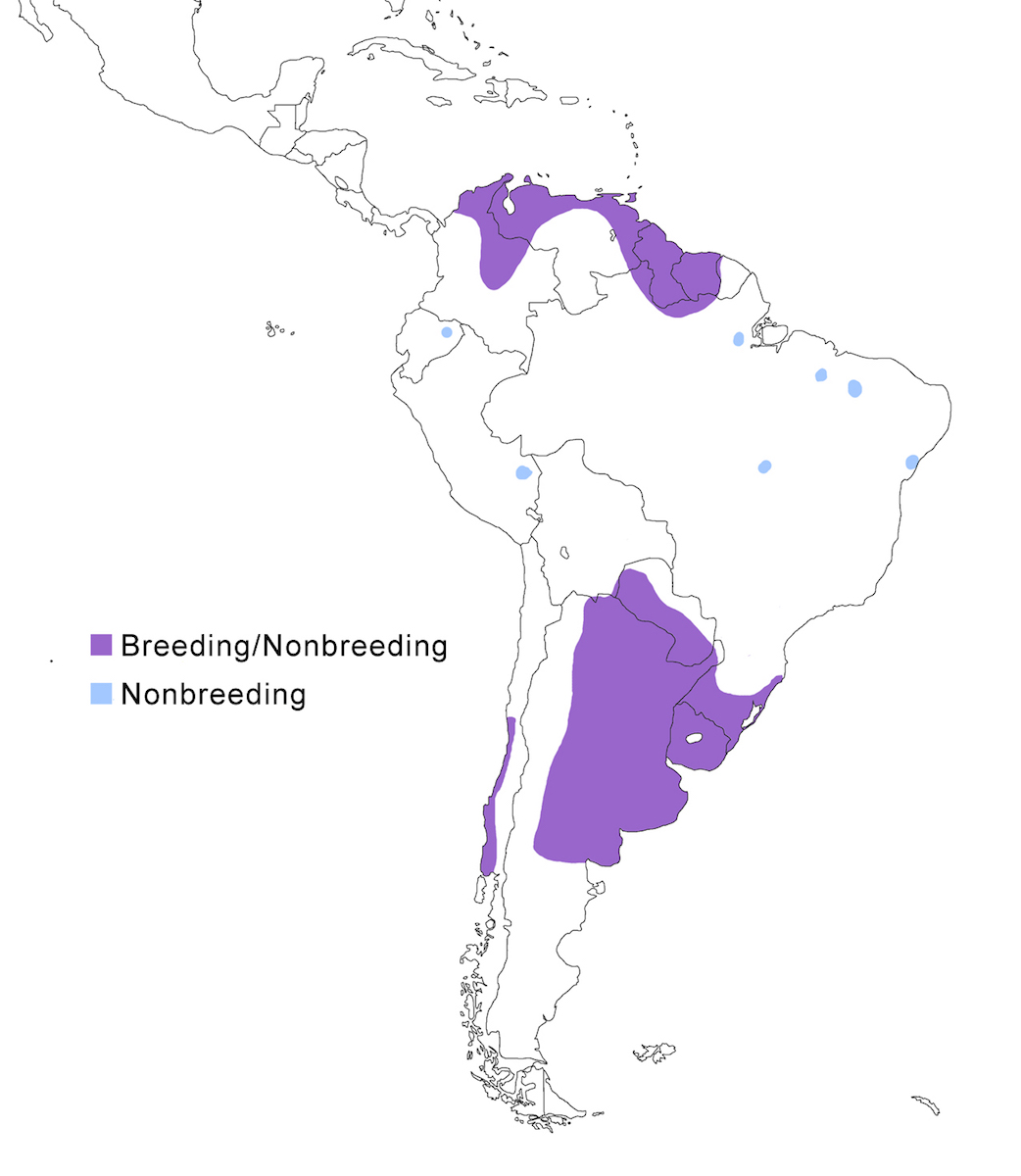

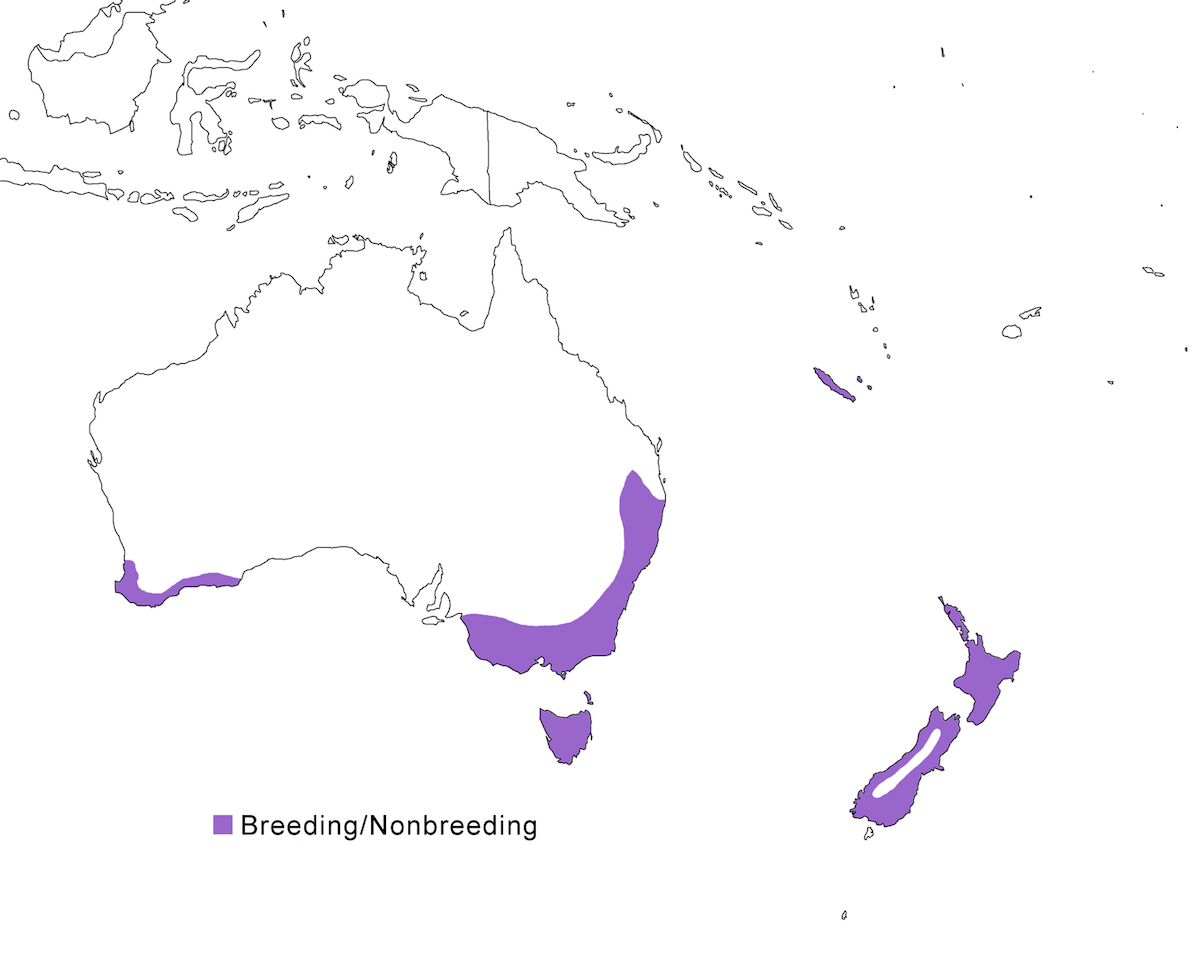

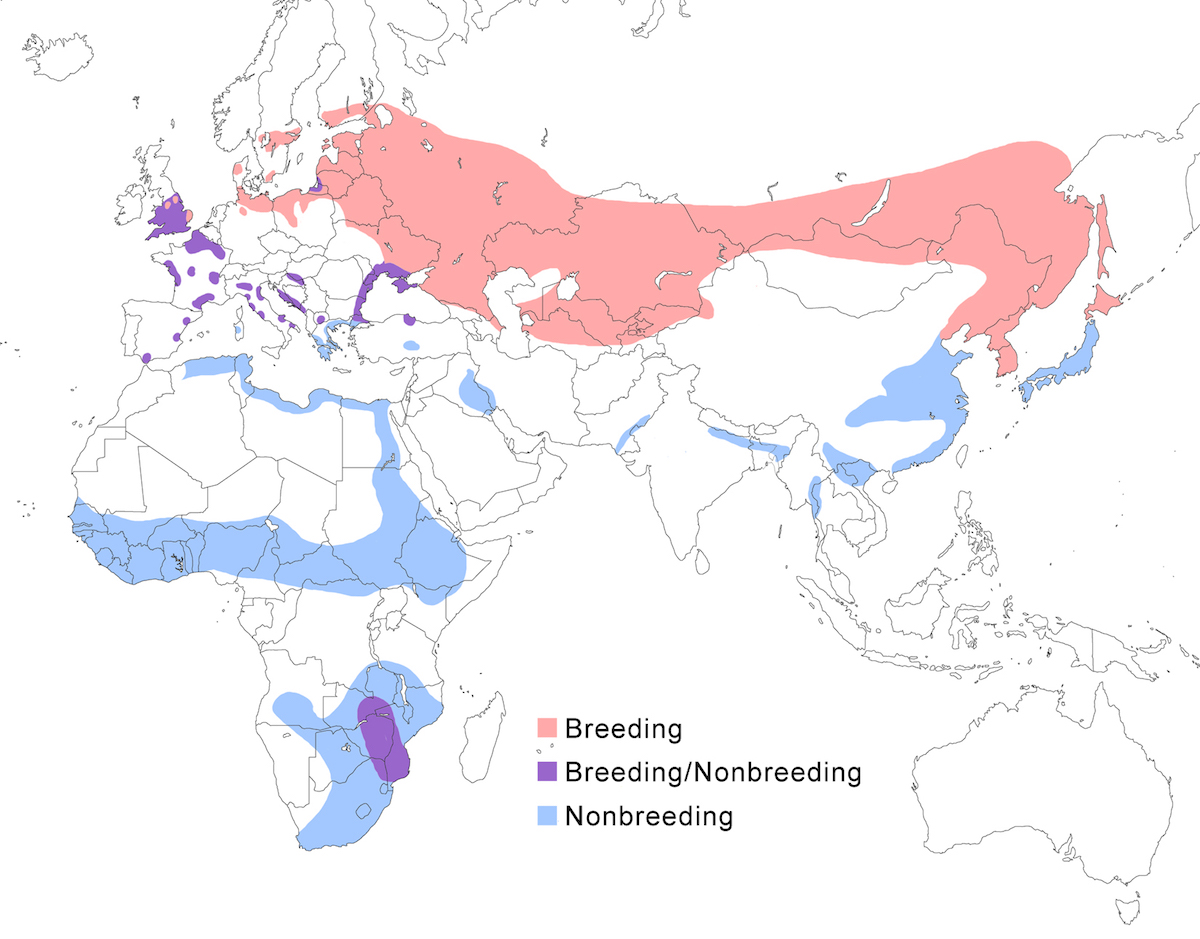

RANGE: The Black Bittern occurs in India, Southeast Asia, Indonesia, Philippines, Australia, New Guinea to the Solomon Islands.

Breeding range: The breeding range of flavicollis is Pakistan (Sindh), India (Jamdar and Srivastava 1990), Maldives, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand (Round 1992b, 1995, Lansdown et al. 2000), Cambodia, Vietnam, to central and south China (Yunnan, Hainan, Guangdong, Fujian, Taiwan, Hubei, Anhui, Shanxi), Malaysia (Sabah, Sarawak, Indonesia (Sumatra, Timo), Philippines. Australis occurs in Indonesia (Moluccas, Irian Jaya), Papua-New Guinea (including Bismarck archipelago), coastal Australia (north Queensland to New South Wales – Morris 1971). Woodfordi is confined to the Solomon Islands.

Nonbreeding range: Northern populations in China are migratory, wintering in western Malaya (peninsular, Sarawak), through Indonesia (Lesser Sunda Islands), and Philippines. There has been no recorded breeding in south west Western Australia since the 1950’s (Marchant and Higgins 1990).

Migration: Chinese birds move south in October to peninsular Malaysia, Greater Sundas and Philippines. Return is April- May. Post-breeding dispersal occurs and is likely the origin of island populations of this species. In India post breeding dispersal and drought based movements occur. A Malaysian bird has been recovered in India (Manipur) and an Indian bird was recovered in Maldives. Australian birds appear to be sedentary, but some regional movements occur. Dispersal records include Japan (Fukumoto et al. 1992), Christmas Island (Indian Ocean), Mollucas, Guam (United States).

Status: The status of the species is unclear. It is common in Pakistan, parts of India, and Sri Lanka. It is common and abundant in Myanmar and southeast China (Lansdown et al. 2000). It is widespread and not uncommon in east Australia but has declined over the past 50 years due to destruction of river edge habitat for farming, pastures and also because of salinization (Marchant and Higgins 1990, Maddox 2000). It is common in winter in Sarawak (Malaysia). It is uncommon in winter in Sumatra (Indonesia) and Philippines. It is widespread in New Guinea.

Habitat

This species typically uses thick scrubby vegetation, particularly forested streams and pools in permanent wetlands. But it uses a variety of habitats including swamps, mud flats, reed beds, wet forests, flooded bushy areas, marshes, forested streams, Pandanus fringed channels in swamps, Melaleuca swamps and coastal mangroves in Australia. Although primarily a lowland species, it occurs up to 1,200 m in India. It winters in reed beds around lagoons, pools and reservoirs in peninsular Malaysia and Borneo. It uses trees and reeds to rest and roost.

Foraging

The Black Bittern forages singly or as a pair in thick vegetation. It feeds by Standing with its neck and head pulled in and by Walking Slowly in Crouched or Upright postures (Recher et al. 1983). It also can scuttle agilely along mangrove roots and creep stealthily in a distinctive crouch. It feeds crepuscularly and also during the day when it is overcast or rainy.

They are seldom seen because they hunt in densely vegetated marshes and creek edges. When disturbed, it runs into cover or flies away. They roost when not foraging in reeds, trees or on the ground.

Food items recorded include relatively large fish, 12 to 115 cm long (Perca, Amniataba, Gobiomorphus), frogs, lizards, crabs, crayfish, shrimp, mussels, and insects including dragonflies, beetles, and flies.

Breeding

Nesting timing differs geographically. In the north, breeding is triggered by the advent of the monsoon, at any time between May and September. In Sri Lanka nests have been found in April, May in Java, February in New Guinea, and September to January In Australia. Overall it breeds in densely vegetated, secluded wetlands. But its nesting habitat is surprisingly diverse, depending mostly on having dense cover near water. In India and Sri Lanka, it nests in reeds, thorn bush or cane breaks low over water. In China, it nests in bamboo and trees as high as 6 m. In Australia nests are located in gums standing in water and in mangroves. It occasionally nests away from water and is it not unusual to nest close to human habitation.

Black Bitterns nest solitarily or in loose nesting groups. At places the nest interspersed in mixed colonies with other herons. The nest is a platform, 23-35 cm wide and 7.5 cm, with a shallow central depression. It is made of twigs or reeds. The nest is built by both birds. Its placement is variable, from 1 to 15 m above the water or ground.

Little is known about the courtship of this species. It adopts the Bittern posture when disturbed and when alarmed, raises and lowers its crest. It is likely that the plumes at the base of the neck are used during courtship display, but there is no information.

The eggs are white, although there have been reports of a blue tinge to some. As recorded, they vary in size averaging 41.6 x 31.4 mm in India and Myanmar, 45 x 35 mm in Australia, and 43 x 34 mm in New Guinea. Clutch size is 3-6 eggs. Although it is probably usually single brooded, double broods occur. Incubation is by both sexes. Both sexes feed the chicks regurgitated food. The incubating bird sits very tightly and the chicks. The chicks soon leave the nest if disturbed.

Nothing is known about late nesting.

Population dynamics

Nothing is known of the population biology and demography of this species.

Conservation

In Australia the species has declined owing to clearing for agriculture and the increasing salinity of the rivers. It was once common in southwest Western Australia but is not known to have bred there in 50 years. It is widespread elsewhere in Australia, but Garnett (1992) listed it under Taxa of Special Concern. In NSW it is listed (updated 1999) as Vulnerable under the NSW Scientific Committee Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 and in Victoria its conservation status is classified as Critically Endangered (NRE 2000). The actual breeding distribution is little understood and not quantified. In many cases the range is based on a few observations. A basic conservation need is to clarify the breeding locations and distribution of the species and to locate the most important breeding areas.

Research needs

Patterns of geographic and individual variation are not clear. The variation in plumage and size in this species needs to be re-examined. There also is a need to clarify the status of the species throughout its range.

Overview

The Black Bittern is a forest bittern, a bird of thick cover, generally scrubby vegetation along mangrove shores and other watercourses. It is not a river heron in the sense of using running water, but thick vegetation along water courses appears to be a habitat requirement. It feeds in normal bittern fashion, but is relatively large for a ‘small' bittern. With its long bill and neck, it appears to be a fishing heron, working along the banks of watercourses from vegetation. It appears to take relatively large prey, and so may not eat large numbers of prey items per day. It likely feeds from territories, which it knows well and undoubtedly defends. Much remains to be learned about this heron.